by Amya Diggs

As a child, I was shy, sometimes a little mean, but definitely very empathetic. I was often crying about something or worried about other people to the point that I would feel sick, and I had no idea how to control any of my intense emotions.

I felt deeply about everything and everyone. I remember seeing people experiencing homelessness in an open field off the side of the road each time I went to Costco with my grandmother; I wondered if they had families who loved them to go back home to; and every time the wind, lightning, and thunder scared me during rich mid-July storms, I found myself wishing for some way to make sure that each of them had a safe place to stay as it poured through the night.

Why are they always camping? They need new tents! Theirs are falling apart.

As I moved from elementary to middle school and then high school, my worries expanded. I began to learn about the histories and current events surrounding human rights. Issues within immigration, racism, gender equality, healthcare, access to education, climate change, LGBTQ rights, etc., all fascinated and consumed me. My love for people and equality continued to grow the more that I learned.

Towards the end of my high school career, George Floyd was murdered, and the Black Lives Matter movement reached its peak as thousands of people across every state took to the streets to protest police brutality. Through seeing my family, friends, and community block streets off in our small city to support Black lives, I realized how much people can care for each other.

Watching communities across the country show up to support and demand change for the painful struggle for Black liberation is the most empowering thing I have been a part of. As time went on, people’s passions for seeing change dwindled, but mine only continued to increase.

I began to recognize these social justice issues as the effects of existing and living within a system that prioritizes profit over the wellbeing of people. By the time I started high school, I did know that those people I saw on the way to Costco were experiencing homelessness, but I finally started to understand what I was seeing as the effects of a housing crisis.

My questions shifted from “why are they always camping” to,

Why are these systems failing our people? Why can’t we do more?

When I left home in Maryland to move to Boston for college, I was required to take a first-year seminar class for the Honors Program. This program requires first-year students to complete a thesis of twenty pages. I had never written anything close to twenty pages in high school, so the thought of writing that much terrified me. Many of my classmates wrote about issues within popculture including exploring sexist movie tropes and the sexualization of music artists.

I was interested in writing about something less media related, and I knew I wanted to highlight Black women in whatever I wrote about. I ended up writing my thesis about Black women’s maternal health, specifically in Boston, focusing on the disproportionately high death rates of Black women and children.

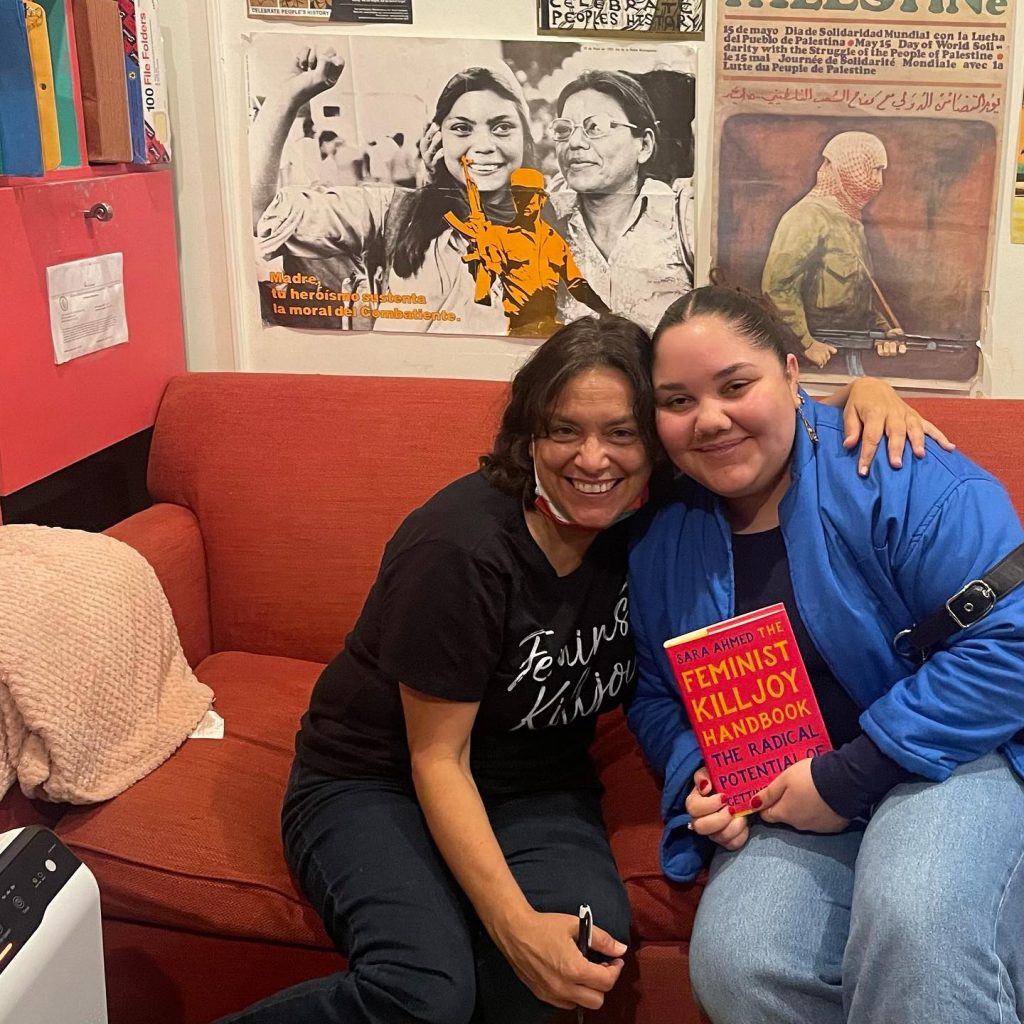

Early on in this research process, my professor, who I am forever indebted to, recommended that I read Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others by Sara Ahmed. After a quick Google search of Ahmed and scrolling through her blog “feministkilljoys,” I knew that Queer Phenomenology was going to be good, and it was. In the piece, Ahmed examines how bodies exist through space and time by exploring how our experiences are physically oriented towards certain directions and objects. She specifically focuses on queer bodies, as the existence of anyone outside of cisgender, heterosexual, white men, disrupts the process of orientation. I’ve cited Queer Phenomenology in several of my academic papers, I’ve recommended it to my friends and classmates, and I am planning to use it again for my senior thesis.

Coined by Ahmed in her book The Promise of Happiness, a “Feminist Killjoy,” at its core, is someone who challenges social norms by speaking out against inequalities, oppression, and injustice. To be a feminist killjoy is to call out your closest friends, professors, and anyone else you hear making offensive comments about human rights.

Putting this framework into practice, confronting people I know, especially people who I am close to about topics that are generally difficult to discuss, has been some of the hardest work I’ve ever done. Now, two years after I was introduced to Ahmed, and a few months into fully encompassing the difficult work of being a feminist killjoy, I finally feel connected to the truest version of myself. Confronting the people around me has forced me to confront myself in times where I would rather just not say anything to those voicing their opinions in ways that are upsetting.

After spending much of my youth confused about my emotions, wondering why people felt inconvenienced by my presence and beliefs, and simply trying so hard for so long to find people who felt the same as me, the words of Ahmed helped me articulate to the world who I am.

I am Amya Diggs—a biracial lesbian, a feminist killjoy, a socialist, a journalist, a creative, and a girl who cares too much about people to stay quiet. I am learning how to balance the act of being a killjoy with still offering people with opposing views the chance to relearn.

I believe that a large part of what it means to be a killjoy is to always be willing to learn—a process that is never truly complete. Because of that, I will be learning how to be a killjoy for the rest of my life, and I hope that I can inspire others to start their killjoy journey as I continue on mine.