Make Lit Class Great Again: Maus and Maus II

Christina Bagni // Blog Writer

Oh, yes, I’m well versed in comic books. I have about three issues of the vintage DC Comics Powerpuff Girls series in my attic, and I casually buy Archies at the supermarket, so clearly I know my stuff. As if you needed more proof, I frequently peruse Garfield, with an occasional foray into Garfield Minus Garfield.

Okay, so I don’t know much about comics. I just never got into them as a kid, and whenever I tried to read them later on I just got confused: do I read the text first, or look at the picture? Are you supposed to read this one backwards? Is it called “comic” or “graphic novel?” How do you pronounce “manga,” and who is “Annie May?”

So anyway, I was naturally pretty hesitant when I saw Maus and Maus II by Art Spiegelman (1980, 1991) on my reading list for US Multicultural Literature last semester. I had them on my Goodreads list for a while, just like Alan Moore’s V for Vendetta, but had never expected to actually read them. I couldn’t get invested in the Pow! Kazam! excitement of superheroes, and I was supposed to read a comic book about the Holocaust? I went into it with the sinking feeling that finishing the books would be like pulling teeth.

I opened the first one, and before I knew it I had passed the page we were meant to read to for Monday’s class. Well, I had time…so I read the next chapter, and the next, and soon I was done with Maus but didn’t want to stop, so I devoured Maus II right away, and in one night I went from thinking I could never get into reading a comic to thinking Maus was one of the most brilliant things I’ve ever read.

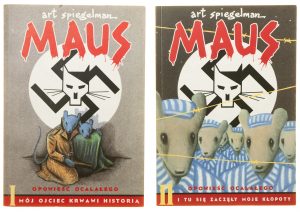

Many people are familiar with the cover artwork of Maus: two mice cowering beneath a vibrant swastika with a cat head in the middle. The symbolism might seem blunt at first—okay, so yeah, the Jews are mice and the Nazis are cats, how creative. But as you read, you see that it’s a far deeper metaphor than originally perceived. Vladek, the main character, is a Polish Jew, and usually Polish people are portrayed as pigs. However, he and his Jewish wife are seen as mice and have to wear pig masks to hide from the Nazis, suggesting their religion was a more important part of them than their nationality. This allows you to wonder if the animal heads are symbols of what the person thinks of themselves, or what others see them as. There are plenty of literary elements in Maus, even in its non-traditional form.

The art is amazing as well. Little details, like the prominence of maps, interesting angles, the use of shadows, and the incredible amount of emotion Spiegelman manages to show through the simple mouse faces bring the story to life in a way far more powerful than plain words or plain film could achieve. A prominent example is the moments when Vladek, in the present, reaches for something, and you subtly catch a glimpse of the tattooed ID number on his forearm, a detail that may have been missed in quick-moving film, or would have had to have been made more prominent in text.

It should have been obvious to me that some stories work better in the medium of graphic novels, just how some stories work better in book form or in movie form. Being able to read the true story of Vladek Spiegelman surviving Auschwitz at my own pace, but still with enticing visuals, allowed the story time to sink in and have a deeper impact.

The story is told in flashbacks, with a main narrative of the author interviewing his father in the “present” (the 70s), and then flashbacks of the Holocaust interspersed, narrated by his father. These narrations are transcriptions of the real-life interviews between Art and Vladek, which you can hear parts of online and in the companion book, Meta Maus. The reality of the stories portrayed also bring up the question of heroism; Vladek survived the Holocaust and did plenty to save his wife as well, but he did so by often being incredibly selfish, and it is shown in the “present” story that he often annoys his son and is actually quite racist. Is he a hero, even if many of his actions aren’t heroic? Maus plays with the idea of heroism in a way I hadn’t really seen before.

It’s also incredibly self-aware. In Maus II, which was published a few years after Maus (and after Vladek’s death), Art talks directly to the reader, explaining his guilt for profiting off his father’s struggle and ultimately furthering his career by exploiting the terror of the Holocaust. He also often adds in bits of humor, which are much-needed and well-timed in the midst of such an emotionally taxing story.

Finally, Maus is simply entertaining. Peppered with dry humor and real character, the story is moving and strikingly powerful. It is extremely well-composed, artistic, and educational, and—even with the animal heads—it is a very accurate portrayal of the Holocaust.

If you’re like me and don’t read comics/graphic novels, I would say this is a great place to start. If you already like the medium, definitely give Maus a go. Though I don’t have many comics to compare it to, I can say with utmost certainty it is far better than Archie. Do with that what you will.

“Make Lit Class Great Again: Maus and Maus II” is a fantastic take on how graphic novels like Maus can deeply impact readers. The analysis of symbolism and storytelling truly highlights their literary depth. A great read for anyone exploring non-traditional narratives!