Stricken Ill with Ferrante Fever

Kyle Labe//Blog Writer

In Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay, the third installment in Elena Ferrante’s triumphant Neapolitan Novels, the narrator lists for a page everything she wants to do away with, everything on which she’d like to “spit”: Hegel, Marx, Lenin, Freud, historical materialism, Nazism, Stalinism, terrorism, war, the class structure, socialism, Communism, and, as the narrator states, “all the manifestations of patriarchal culture…[and] all its institutional forms.” It reads with a seething, boiling rage. She’s pissed off, and she has every right to be.

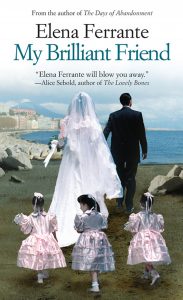

The Neapolitan Novels chronicle the friendship and lives of Elena “Lenu” Greco and Raffaella “Lila” Cerullo, two women who grew up in a poor neighborhood in Naples, Italy. The first book, My Brilliant Friend, opens with the news that Lila has, without any trace, gone missing. Believing this to be a willful decision—as Lila, in her later years, revealed a desire to disappear—Lenu takes on the challenge to write and publish their life stories.

This action of Lenu’s, like any great friendship, possesses both love and spite. Lenu, from a place of admiration, forces herself to write with candor and complexity about her friend, assigning herself the daunting task to produce multiple volumes devoted, and seemingly dedicated, to their relationship. But there’s an irritation, too, and that’s where the best parts of the Neapolitan Quartet emerge. Lenu knows that Lila wishes to vanish, rootless, to die in anonymity and to leave the planet as she entered it; yet she immortalizes Lila in words. It’s a competition between them, a game that manifested from their earliest days as schoolchildren in Naples.

These books Lenu writes represent something much larger in the Neapolitan Novels. It’s a microcosm of rage and love, asking the question if one can exist without the other, and it transcends both setting and characters to symbolize the world as a whole. These are not simply individual Italian women unhappy and bored with their lives; they are to constitute every woman on the planet, and Ferrante feels they’re justified to be enraged at how society treats them, how the world ousts them, how everything we do or say is tinged with misogyny.

Very rarely have I, personally, read a female character portrayed so mad. And not “mad” as in, for example, Bertha “Madwoman in the Attic” Mason from Jane Eyre, but “mad” as in angry, irate, explosive, the latter describing this series to perfection. One of the blurbs on the second installation, The Story of a New Name, reads, “Imagine if Jane Austen was angry, and you’ll have some idea of how explosive these works are.”

Beginning in the mid-twentieth century, the series spans across decades until the new millennia, following computerization, social movements, cultural development, economy, gender relations, and more. The setting of Naples breathes with life, and each character bleeds off the page and into reality. Ferrante’s writing—translated into the English by the masterful Ann Goldstein—flows with modernistic rhythm, breaking convention, rules, and standards. Yet it’s not hard to read. Even with countless characters (there’s pages, before each story starts, outlining family trees and character names) each is vividly described, so individually unique and important that, even when they disappear for 200 pages, when they return it’s as if they never left at all.

With so much to consume—Ferrante covers feminism, Communism, Fascism, factory strikes, religion, poverty, literature, sexuality, women’s friendship, motherhood, marriage, technology, and more—my interests kept returning to its depiction of anger. You can turn to any page of any book in the literary canon and find its male characters are permitted anger: 1984, The Outsiders, The Godfather, The Great Gatsby, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. The list goes on and on. But when, if ever, are female characters afforded the same liberty to feel? Are women ever truly allowed—in literature, in life—to fully express the entire range of their emotions?

Especially within storytelling, and in all forms of it, female characters are reduced to feeling one thing. They can be sad, or happy, or jaded, or afraid; but they can never feel all that, and more, at once. Female characters rarely express dissatisfaction in more ways than one. Ferrante flips the script on this, and it’s refreshing. She achieves this in such a means that, rather than gawking at the freshness of Ferrante’s works, the reader is left questioning why so many authors have not caught up to her.