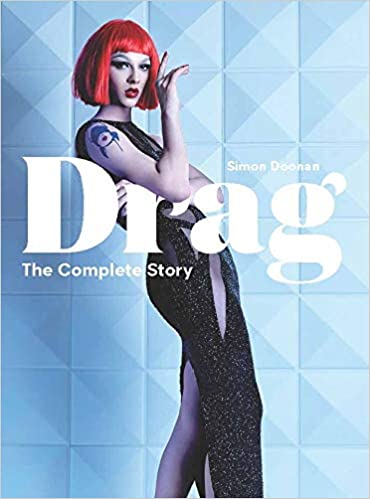

Drag: The Complete Story?

Alli Armijo // Blog Writer

Drag is a cultural phenomenon popularized by the hit TV show RuPaul’s Drag Race. But what Drag Race does wrong is provide a misconception of drag as an art form. After all, drag queens—whether they “specialize” in pageantry or comedy—are not all drag has to offer. So while the show brings drag into the mainstream in a way that is arguably more palatable to a predominantly white cis audience, what is the cost?

In his book, Drag: The Complete Story, Simon Doonan identifies and explores multiple subcultures of drag, pointing out that the glamour queens of RuPaul’s Drag Race are hardly a holistic representation of the drag scene. The nine specific subcategories he identifies are: Glamour, Art, Butch, Black, Historical, Comedy, Popstar, Movie, and Radical. What is so compelling about the way Doonan outlines each subcategory is his obvious reverence for how each unique style contributes to how drag has progressed into the phenomenon it is today and how history has contributed to its current reception.

He also delves into why people are so intrigued by the art form, calling on psychological findings from researchers like Freud. For example, he uses the myth of Medusa to explain that one of the reasons drag queens are so mesmerizing to an audience is because they are “lethal divas” and exude “taboo notions of fierceness, seduction, sadism, and destruction” (137). They challenge social norms and embrace fluidity as it pertains to gender, sexuality, and the like. By making this comparison, in addition to many others, Doonan shows why drag is inherently political and why it is so relevant, especially in our modern society. It will always be influenced by race, sexuality, and gender—and I believe that is why it continues to flourish as an art form.

One thing I appreciate about the way Doonan outlines the information about the history of drag is the structure of his work. Each chapter bleeds into the next, highlighting how specific approaches to drag have influenced the art form both in the past and in current conditions. Specifically, the chapter on Black drag takes drag culture a step further, going into how Black drag has influenced LGBTQIA+ culture as a whole. Doonan outlines specific icons, such as Pepper LaBeija and Jackie Shane, both of whom confronted discriminatory cultural and social norms through their presentation and language on stage. With this, he also draws upon Black trans performers who have elevated ball culture while simultaneously establishing themselves as icons in the art of drag.

One of my personal favorite stories came from the legendary contributions of Vaginal Davis, a proponent of “terrorist drag” who embraced gender non-conformity by challenging and exploring racial and gender confusion through art and drag.

Overall, Doonan employs witty anecdotes throughout, ensuring the information is not buried under antiquated language and a stuffy tone. His prose is approachable and light-hearted, making it easier to connect both to the content and his authorial presence. In doing so, he makes drag accessible and fun. Additionally, his personal experience in the club scene and relationships with drag performers allow him to approach the subject from a familiar, comfortable perspective. He does not come across as an academic who specializes in drag, though this does not take away from the validity or depth of his research.

By dedicating whole pages and chapters to less common drag performers and trailblazers, Doonan again shows that Drag Race did not write the history on drag. However, he does not in any way diminish the impact or importance of queens who have graced the Drag Race main stage. After all, exposure from drag race has undoubtedly led to increased acceptance of drag as a form of art, political activism, and expression—it is just not the only source, or history, of drag as an art form.