Unload the Canon

Julia Brukx // Blog Assistant

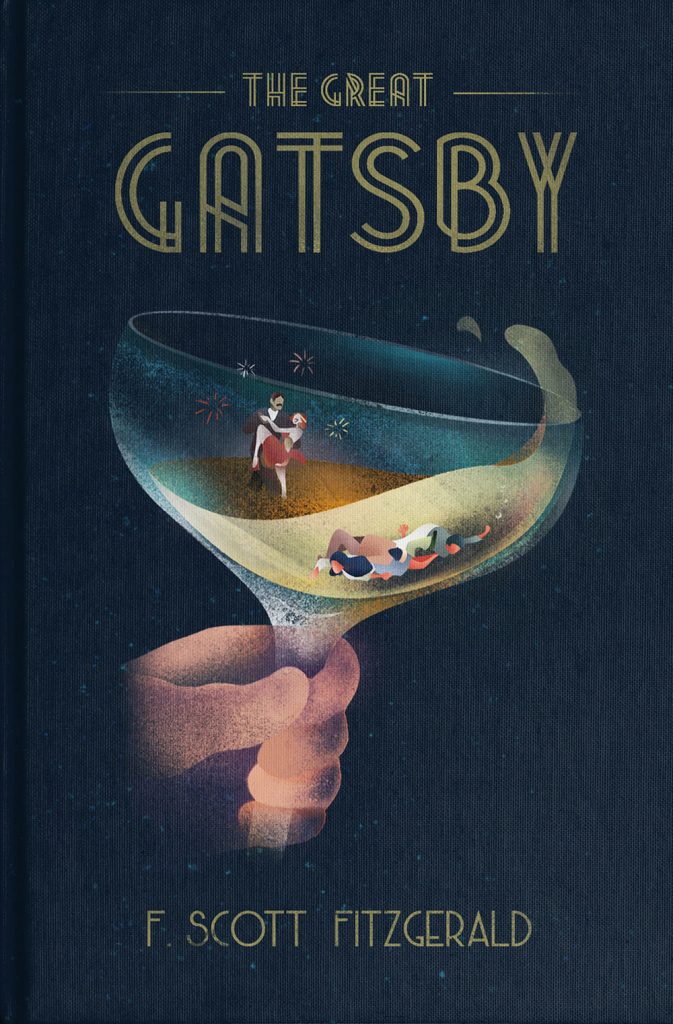

On January 1, 2021, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s chef d’oeuvre The Great Gatsby entered the public domain. First published in 1926, the statute of limitations had passed for Gatsby to remain in the possession of Fitzgerald’s cold, dead hands, releasing the novel to the public for whatever uses they see fit. Though the past 95 years have seen no shortage of adaptations—from the Baz Luhrmann andLeonardo DiCaprio classic to an off-Broadway musical— Gatsby’s entrance into the public domain represents a new era in which anyone and everyone can make their own interpretations. Already we have seen a graphic novel, a zombie reimagining, and countless new editions with gorgeous covers. Undoubtedly great art will come from the source material, which begs the question: how long must we wait before we can simply toss it out?

The Great Gatsby is a relatively simple story. A thin paperback coming in at under 200 pages, it tells the story of Nick Carraway and his exploits with his new neighbor Jay Gatsby, his vapid cousin Daisy Buchanan and Daisy’s husband Tom. Nick attends parties, listens to rumors and treats himself as a passive observer. Like all great parties, though, there comes a moment where the drinks fizzle out and the chaos becomes too loud for anyone to still be having a good time. The affairs must end, Gatsby must die, and the eyes of Dr. T. J. Eckleburg must view all with supreme judgement.

From this simple story, however, tidal waves of interpretations have been launched: it’s a critique of American jazz age consumerism (true); Daisy meant to kill Myrtle (less true); the whole thing is an unrequited love story between Nick and Jay (I’ll leave the judgement on this one to you). The phenomena of “Gatsby parties” have emerged as something that people used to do before the second wave of the ’20s came around, despite the book basically being one long argument against such events. For almost a century now, we have been taking what we want from Gatsby and tossing the rest out. Therefore, we should be well-prepared to fully embrace the new wave of content, whilst purposefully losing sight of our origins.

Is it abandonment of the original canon to say that what has come out of Gatsby is far better than the original text? After all, much like there’d be no chicken without the egg, there’d be no Gatsby: A Musical without Fitzgerald’s original manuscript. And to beg a larger question: how long must we go before we find a new canon of American literature? Before we abandon our Hemingways and Fitzgeralds for Cisneroses and Butlers, must we bid them some sort of farewell?

It has long been known that the classic idea of “the American Canon,” constructed in waves including the Lost Generation, the Beat Generation and the Literary Brat Pack, is far too white and far too male to fairly represent the American stage. However, each time a high school class opens up Of Mice and Men or The Catcher in the Rye, they are asked why these works have sustained, why they remain important to American literature, to the point that it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Gatsby will never exist without F. Scott Fitzgerald’s ghost hanging around it. But perhaps a devaluation of the sacred canon will help work to collapse the idea that there is one club of books that may be read to understand American literature. And maybe an eight-hour stage musical in which Gatsby is concealing a vampiric secret and Nick is recast as a zombie detective is the only way in which that can happen.