Ali Hazelwood Faces Backlash for Writing Process: Should Authors Rely on Tropes?

Ana Garcia-Cubas Assemat // Blog Writer

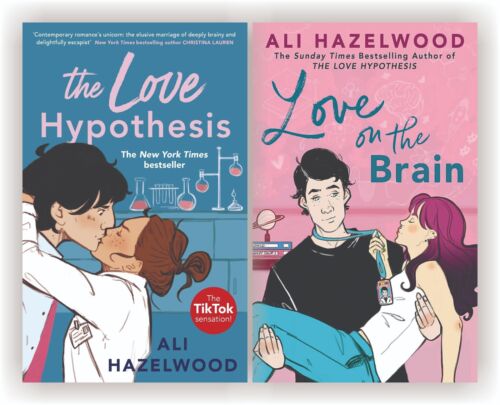

In an interview with Goodreads, neuroscientist and romance author Ali Hazelwood confessed that she struggled to write her second book, which followed the debut that landed her on the bestseller lists. Her first book, The Love Hypothesis, is infamous for having been adapted from Hazelwood’s Star Wars fanfiction starring the Reylo pairing (Kylo Ren and Rey). Before publication, Hazelwood switched Kylo Ren’s name for the name of the actor that played him in the Star Wars movies—Adam—and the text was edited to work as a book separate from the fandom space.

During the interview, Hazelwood discussed how writing fanfiction is different from writing a book “from scratch,” stating that fanfiction is “mostly about the characters and their interactions, so you don’t need to have a story with a first, second, and third act, and the beats, and character arcs.” It was this difference in approach that caused her to struggle with her second book, since she had no existing media to jump off of.

So how did she approach the issue of writing “from scratch?” Hazelwood said that she dedicated a lot of time to reading craft books and studying her favorite romance novels, figuring out what made the work tick and how to replicate that feeling. This is a pretty common approach to writing, as it’s very rare to find an author that doesn’t read anything within the genre they write. Not everyone can sit down and create an entirely new genre for fun (looking at you, Mary Shelley). For most of us, half of writing is reading.

What drove criticism from the literary community was Hazelwood’s following statement: “I kind of didn’t even know where to start, and my agent guided me a lot. […] She gave me a bunch of tropes that she wanted me to build the story around, which was really, really helpful because I am very indecisive and had no idea what I was doing.”

While we can all relate to having a little writer’s block and needing advice from those with more experience, the idea of a bestselling author writing a book based on a list of tropes they were spoon-fed by their agent can seem unconventional, to say the least. This prompted an ensuing discussion surrounding the tropeification of literature and privilege within the publishing world.

The romance genre is well-known for relying on tropes, both in the writing and the marketing aspects of its books. Booktok—one of the most influential consumer bases nowadays—also relies heavily on tropes to recommend books, often including only the title, star rating, and tropes of any given book in a recommendation video. This means that when it comes to selling books, making a clever and evident use of tropes is essential.

The key here lies in clever. While there are many readers who don’t mind reading the same trope over and over again (myself included), there is an expectation that the author will put in the work in other aspects of the story. If the plot is predictable, then the characters had better be interesting. Good characterization, proper pacing, and an engaging writing style are essential; the work cannot stand on its own if it’s built solely on tropes and nothing else of substance.

And reducing genre fiction—such as romance—to tropes is doing it a disservice. The romance genre is so oversaturated and its premises so few that a romance book basically has to reinvent the wheel in order to gain any recognition outside—or even within—the readers of the genre. Although, at times, it may feel like there is no such thing as an original love story, it takes skill to write one that makes the reader feel the emotional stakes in the narrative.

But the latest push towards reducing romance to a handful of tropes means that books like Hazelwood’s don’t particularly need to be well-written to be successful—they just need to use a trope that TikTok is interested in, and pray for good luck.

Regarding Hazelwood’s writing, Kate from the book club Bitch Bookshelf said: “As much as I enjoy Hazelwood’s works, it’s because they appeal to the tropes and topics that interest me as a reader. They are, as a whole, fairly mediocre, bringing nothing new to the romance genre. Sure, there’s always a feminist, STEM spin—but we’ve seen that in other works.”

Many readers seem to tire of publishing’s current approach to writing and tropes, but it is undeniable that these books are very successful, and for the most part, very well-loved. The Love Hypothesis has a 4.28/5 rating on Goodreads and a similar score on Storygraph. It is a New York Times best seller. Who cares if the writing is a little bland and the characters unoriginal? It’s clearly what people want to read.

Now it feels like we’re doing a disservice to the readers, doesn’t it?

Without getting too deep into the argument of literature as an art versus literature as a marketable product, there is another issue that Hazelwood’s statement brought to light:“It is more than okay that Hazelwood, a white woman, has taken on guidance from those she works with to write her novels, but has the same grace been granted to BIPOC authors looking to break into the industry?” asked Kate from Bitch Bookshelf.

Booktok’s success currently drives a great number of book sales, but it is more of a gamble than a science; it is very hard to predict when a book might become Booktok famous. Even before TikTok, authors might not have their breakthrough title until they have had multiple published titles under their belt—most likely with a couple unpublished manuscripts’ worth of experience too.

Considering how white the publishing industry is, it’s worth asking whose mediocrity gets rewarded in publishing. Who gets to write a book that is an insubstantial agglomeration of tropes without their ability as a writer being brought into question? Whose perspective tends to blow up on Tiktok? (Unsurprisingly, a white perspective too.)

“I hope that, as I write more and more, I’ll become a little bit more independent and I won’t have to harass people, but, as of right now, I’m still at a phase in my writing where I really need a lot of help and a lot of guidance. I definitely need all of the hand-holding that I can get!” said Hazelwood. This handholding is a privilege that not many BIPOC authors are afforded.

There is also the matter of trend cycles and profitability in publishing. Hazelwood’s agent clearly wanted to capitalize on the momentum that her debut amassed, but pushing a debuting author to write more than they are able to seems like a great way to constrain their growth as a writer. I wonder what Hazelwood’s original concepts would have looked like had she been allowed to develop her craft without the pressure to ride on the coattails of her past success.

Hazelwood’s interview had the misfortune of highlighting many aspects of publishing that warrant criticism. While I feel bad that she got caught in the crossfire, I do think that these conversations need to happen. Publishing seems to keep moving into the realm of profitability over art: what used to be an industry where breaking even was considered enough is quickly becoming more concerned with maximizing profit rather than with creating cultural materials. This process is leaving both publishers and authors behind as wages and advances stagnate, and marginalized voices get pushed to the bottom of the priority list while everyone is busy renegotiating film rights on the new Booktok hit.