Literary Civil War: Inside the Mad World of Early Surrealism

Guest Writer // Jagger van Vliet

TW: mild violence

It is entirely unexpected that there was once a time in which writers and artists waged brutal war against each other, all in the name of genre. It seems trivial, or even foolish, that artists of the early 20th century should have preoccupied themselves with petty disagreements and bitter rivalries. In truth, nothing appears productive at all about squabbling over a genre of art that is, at its core, meant to mean nothing. Yet, consider that writers, in their very nature, are territorial to a fault and otherwise steadfast in their convictions. It should, to an accustomed writer, seem only natural that such a close-knit group of artists might eventually collapse into infighting and ego. Here, we find the chaos. Here, we find several curious vignettes. Here, we find the great surrealist civil war.

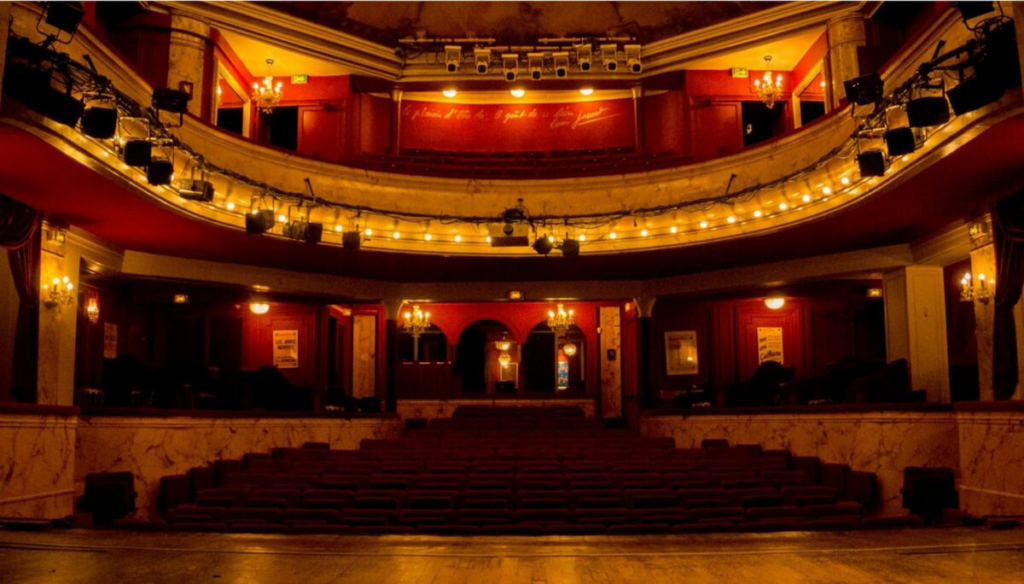

In tracing the schism of surrealists to the inchoate root, we might first observe the famed Night of the Bearded Heart. Having unfolded at the Theatre Michel in Paris, this has been widely accepted as poetry’s most violent night. Many of the foremost names in the Parisian Avante art scene were in attendance. Poets, playwrights, and performers all gathered to witness Tristan Tzara’s newest play. But beneath the surface, there was discontent. Surrealism had not even been given a name, but Andre Breton, a bellicose young man with an increasingly loud mouth, felt that the art movement of the time- Dadaism as it was called- was in need of an immediate funeral. He felt that it was antiquated, unnecessary, or otherwise uninspired. This sentiment was echoed by many of his peers, and so, on the Night of the Bearded Heart, tensions were already at an all-time high. So it was when writer Pierre de Massot took the stage and proclaimed that Pablo Picasso was dead to the art world, chaos erupted immediately. Surrealists and Dadaists came to blows in the centre of the Theatre Michel, where a melee broke out. Andre Breton famously leapt onto the stage and brutally beat de Massot to the point at which he fractured the young writer’s arm. Amidst this chaos, the police were summoned and promptly arrested the belligerent band of artists, marking this night as the death of Dadaism and the birth of something new, something frantically exciting. From this night, surrealism was born.

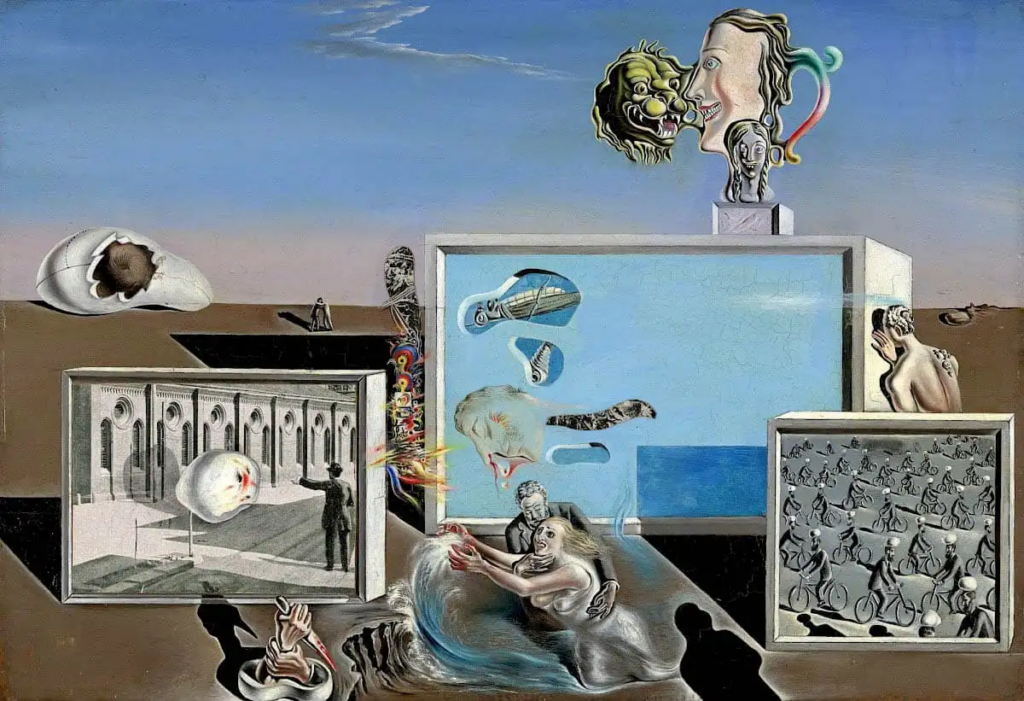

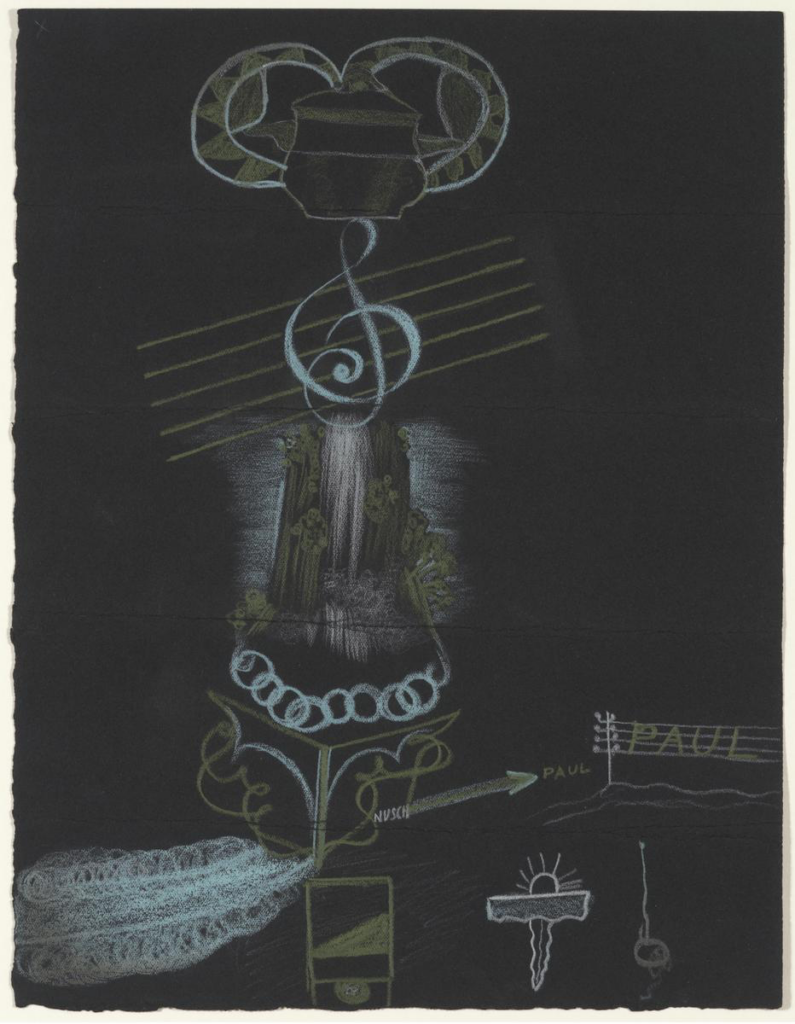

Soon thereafter, the surrealists began a string of media appearances, something to the effect of Surreal Ciruses, or exhibitions wherein these nascent artists could display their new and twisted visions. Amidst teacups made of fur and nightmare confessional booths, Salvador Dali rose to prominence for his increasingly drastic antics. On one such occasion, at a London expose, Dali delivered an extended lecture on paranoia from within the confines of an antique diver suit. Metal bolts were affixed, and he was, for the duration of his speech, entombed in the metal confines. However, not one person accounted for airflow, such that the artist rapidly began to run out of oxygen. Thrashing wildly only excited the crowds, who assumed that this was a grotesque performance of some kind. Only when the helmet was smashed in and Dali was revived did the artist note happily that he was delighted by his “Really deathly pallor.”

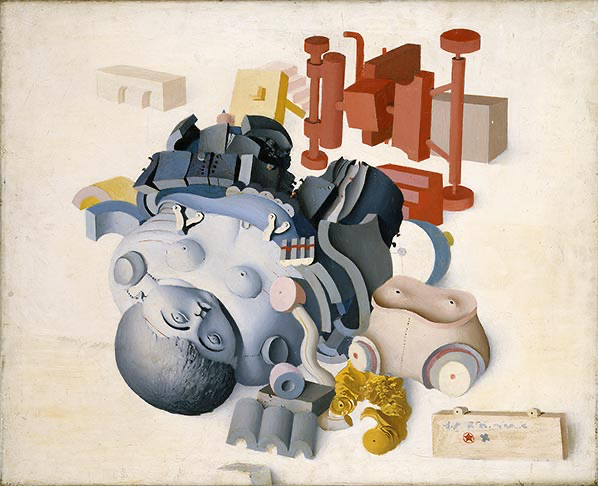

Dali was no stranger to surrealist antics, drawing further criticism for his behavior at the Bonwit Teller & Co. department store display. He had designed the storefront display to show a bizarre scene in which a hideous mannequin lay draped in a fur bathtub and another bathtub was filled with the head and hooves of a buffalo. Deeply disturbed by this image, the storefront altered the original vision, which so enraged Dali that he promptly lept into the display case and sent through the buffalo head, bathtub, and finally himself out of the window.

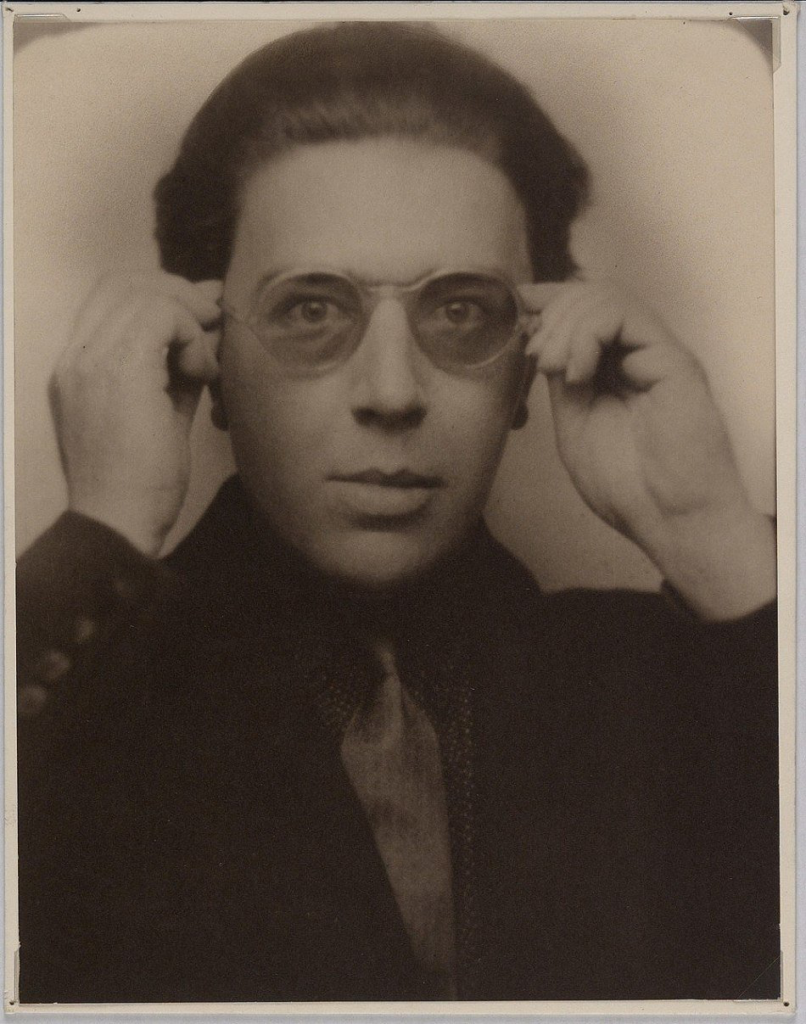

But this was not the first time Dali’s ego came to blows, as Andre Breton soon tired of the artist’s increasing antics. Having drawn the final line at Dali’s selling of his own autograph for ten dollars, Breton expelled his peer from the Parisian surrealists. Not only this, but Breton also coined the term AVIDA DOLLARS, which not only translated to “Hungry for money” but was also a clever rearranging of Salvador Dali’s own name. Completely nonplused, Dali referred to this as “The only truly brilliant idea Breton had ever had.”

Amidst these antics, many events were staged by Breton and the surrealists, and these events garnered much media attention for the increasingly upsetting acts performed on stage. In particular, Andre Breton was heckled and jeered at as he read a portion from Picabia’s Manifeste Cannibale. The ever-irascible Breton famously lashed out, mocking the crowd in a cruel fashion and turning the night promptly on its own head. Here, the crowd became soured, proceeding to hurl rotted fruits at the Breton, who took this moment as a sense of ultimate triumph.

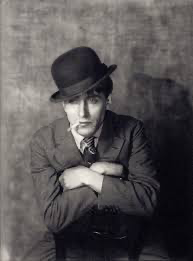

It appears that the natural progression of any surrealist movement, or rather, any surrealist leader, is to be naturally assassinated by their contemporaries. This happened once to Tristan Tzara, who watched as Dadaism died before his very eyes, murdered by Andre Breton’s surrealists. And yet, perhaps blinded by his characteristic bravado, Breton fell out of favour with the surrealists in the years to come. Having made certain scandalous comments in his second surrealist manifesto (in which he stated that the simplest surrealist act would be to descend into the streets with a revolver and shoot people at random), Breton was the subject of intense scrutiny from the likes of Georges Limbour. Here, Limbour claimed that Breton was not only a hypocrite but also a cop and a priest.

These have only been a short collection of the surrealist feuds, and still, they are continually and increasingly bizarre. Fueled by petty rivalries or other ideological disagreements, it would appear that a movement based upon uncertainty is plagued by its own nature. Surrealism, Dadaism, or whatever else should fall beneath this umbrella of art is intrinsically not meant to be defined. This writing is subconscious, subversive, and subjective to a fault. It cannot be governed, classified, or sorted. It is the great, ongoing failure of surrealists- their inability to realize that this art exists as a means of connection rather than intention. No surrealist can mean anything for certain, and yet this in itself is a paradox. Surreal art must breathe, live, and die in a cycle, separated from the figures who birth it to life. But this, too, is impossible. And so, it is only natural that these feuds will go on indefinitely, a naturally occurring byproduct of true and beautiful art form.