Writing What You Know: Should Authors Write Outside of Their Demographics?

Blog Writer // Parker Greaves

As I’m sure many of us are aware, Twitter (and every website like it) is a feeding ground for all the discourse the internet can possibly offer. It’s an American tradition to viciously tear apart all our most famous Hollywood celebrities at the first sign of imperfection, but in 2025—the era of the opinion-based internet—it seems that no one is safe, not even people that previously would not have been on the public’s radar. The accessibility of public personas has encouraged the rest of us to pass judgement more liberally and regularly than ever before, and as a result, cancel culture has expanded from its original focus on A-listers to more niche celebrities—namely, authors.

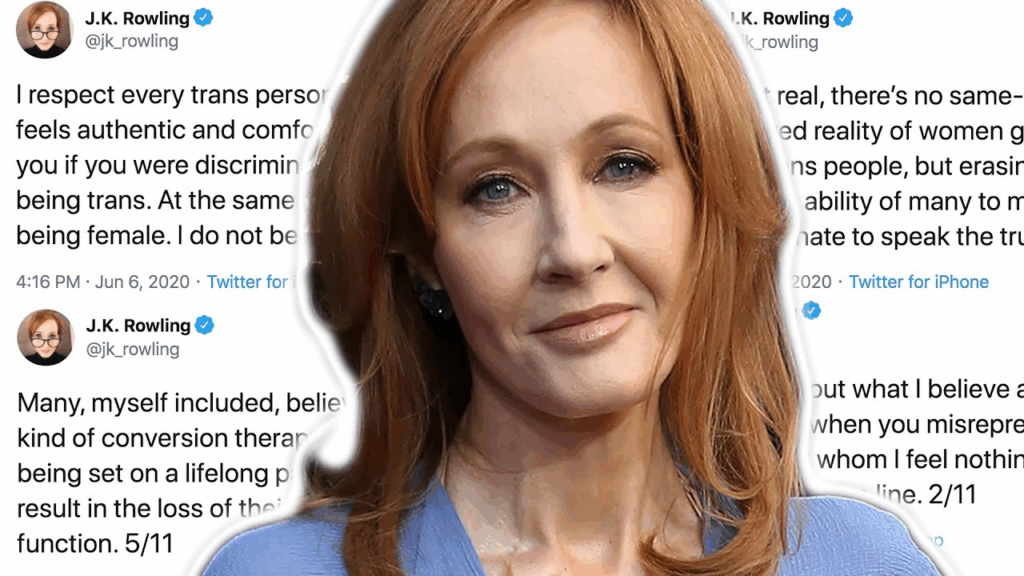

Some of these complaints are valid (I, for one, have been known to scroll J.K. Rowling’s comment sections and take a perverse pleasure in watching her get dunked on), but others fall into more of a gray area. One of those gray areas is the concept of “writing what you know.” People have taken issue with authors who write characters that have a different ethnic, racial, sexual, or gender identity than their own, questioning whether a fictional character can really be “good representation” if they’re written by a person with no particular connection to the struggles they face.

When people refer to “bad” or “problematic” representation in books, they’re generally referring to characters that display harmful stereotypes about the identity group they’re part of. This is often evaluated in how the author writes about the characters. Authors have been criticized for how they choose to describe characters of color, or for how they portray a delicate situation. Colleen Hoover, for example, has been cancelled a thousand times over for her romanticization of domestic violence in her books.

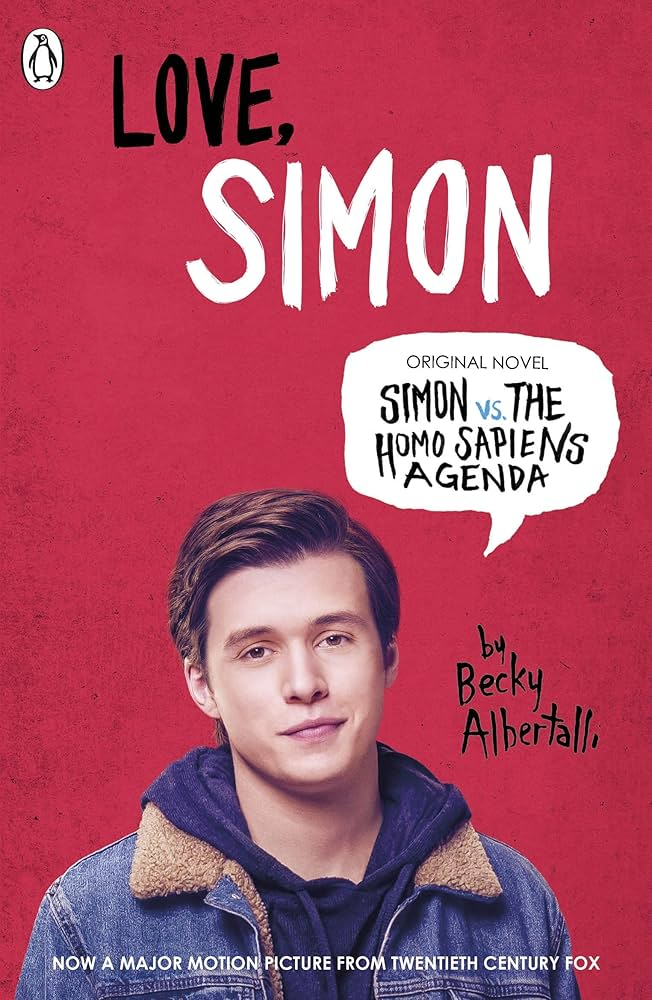

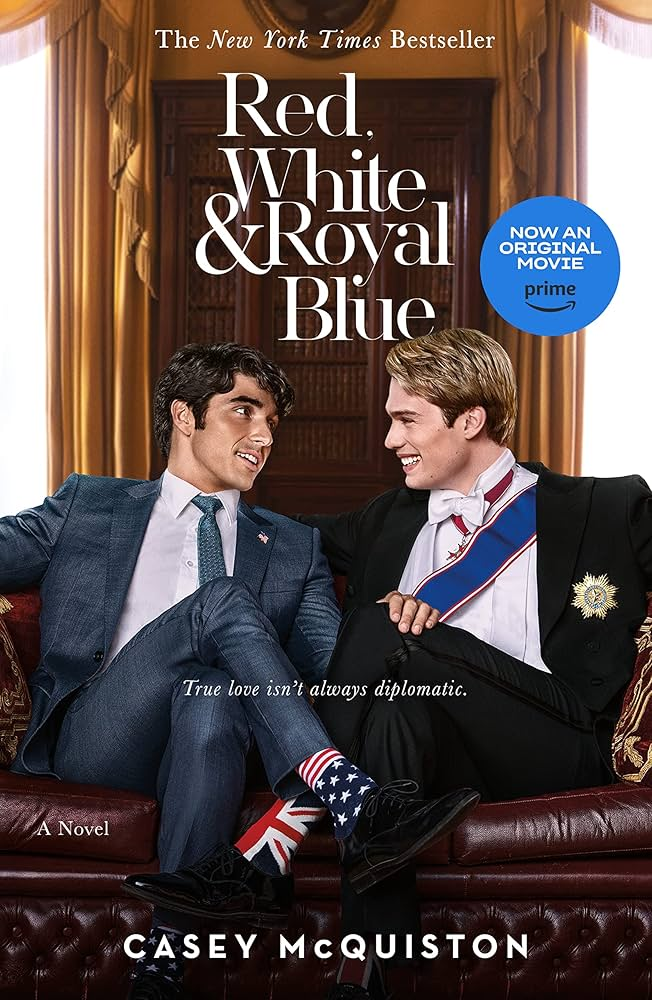

On the flip side, there are cases like that of Becky Albertalli, author of Love, Simon and a host of other queer YA novels. When Love, Simon came out, she was criticized for writing a gay love story from an allegedly straight perspective, and it was claimed that the writing was insincere and invalid. As a direct result of this harassment, Albertalli was forced to come out as bisexual, at which point people retracted their judgements of the novel. The same judgement was later passed onto Casey McQuiston, author of Red, White, and Royal Blue, who has also since come out as queer.

There are several nuances at play within this topic that I think are important. The first is the difference between biased writing and bad representation. Writing with a prejudice typically is shown through the form of language around characters of marginalized groups (How are they described? What’s their backstory like?) while “bad” representation is a far more subjective critique. I think an unfortunate side effect of the current online landscape is the way that it’s made people accustomed to being catered to. Algorithms exist for the sole purpose of feeding us exactly what we want to see, and it’s created a sense of entitlement that seeps into discourse like this.

Sometimes, a fictional character’s experience might not line up exactly with that of a nonfictional person with the same identity, and the reader takes it as a personal offense. However, failure to represent one person’s experience is not the same as a character being a bad representation of the community as a whole, because the truth is that no singular character can accurately represent everyone in a group. The solution to the representation problem is about getting more representation out there, not perfecting what currently exists.

Secondly, we need to acknowledge the way that celebrity culture has infiltrated literary spaces in a negative way. Any literary theorist will tell you that when analyzing a text, the author is meant to serve as a function by which we understand meaning, rather than an all-knowing creator who must answer for everything included in the text. Whether we need to marry ourselves to that concept as casual readers is another discussion, but there is a stark difference between the concept of author-function and the way we treat authors on the internet now. Every line in a piece of writing is treated as a metric by which we judge the author, and when an author isn’t (or doesn’t appear to be) a part of the demographic they’re writing about, the lens becomes that much more scrutinizing.

I think the best way to strike a balance with the cancel culture approach that has emerged in regards to authorship within the past few years is by evaluating stories on their own merit. That is to say, let’s forget about the author for a second, whoever they may be. Instead, think about how the character functions in the story. Are they engaging? Does the story work? Is the portrayal accurate? If the answer is yes, respectfully, who cares who the author is? They’ve achieved their goal. If the answer is no, the criticism can and should still lie within the constraints of that particular novel and that particular writer, not be broadened to a hard-and-fast rule the way the internet loves to do. “This character is a harmful stereotype” lends itself to a much more productive conversation than saying “this author shouldn’t have been allowed to write about this topic, and in fact no authors should ever write about topics they don’t understand.”

It’s important to remember that the word “allowed” is not actually applicable here. Everyone has the right to free speech, and authors don’t have any obligation to bend to public opinion when writing. Placing sanctions on what “can” or “should” be written about obstructs creativity more than encourages it. Free speech doesn’t mean one is free of consequences, of course; no one is ever safe from criticism, and it’s important to call out harmful messaging when we see it, but books should not be dismissed based solely on an author’s identity. Telling someone that they’re only allowed to write about things that they personally experience isn’t just damaging to the diversity of books in general, it also demotivates learning and growth.

“Write what you know” doesn’t need to refer solely to personal experience; if you want to write about something that you don’t have a deep understanding of, there’s nothing stopping you from doing research or talking to people who do understand it. We read and write novels for lots of reasons—to understand our own identities, to understand other people’s, to escape for a while, to learn. If everyone only wrote what they “know” all of the time, the literary landscape would be, quite frankly, boring.