The Origins of Publishing, Part 2

Victor Morrison // Blog Writer

As mentioned in my previous post, progress in the printing and publishing world did not cease after the invention of Gutenberg’s printing press. In fact, print media really took off after Gutenberg, as a huge boom in book and news publishing occurred in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. In 1534, Cambridge University Press became the world’s first publishing house, and it is still in existence as the second largest university press in the world. Cambridge University Press published its first book in 1584 titled Two Treatises of the Lord His Holie Supper.

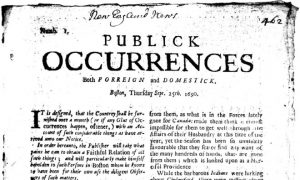

Besides books, news publications also became more common. In 1605, the first newspaper titled Relations was published in Germany, and, in 1690, Publick Occurrences was published in America. America, however young at the time, did not lag too much behind Europe when it came to published material. Compulsory education laws had a big part to play in this, as in Europe and America school started to become a requirement, and consequently, literacy and a thirst for knowledge grew.

But these popular publications were not just limited to books and newspapers, as the first magazine soon made an appearance in London. Gentleman’s Magazine, founded and first published by Edward Cave in 1731, was a general-interest magazine geared toward men. The magazine first drew from other publications before creating its own material, and it was very text-heavy, quite unlike the colorful, captivating magazines we think of today. The magazine ceased production in 1922 after laying the foundation of what a magazine should be and serving an impressive run of almost 200 years.

As the 1800s approached, the printed word was reaching more people than ever before, but the increase in a literate audience did not come without some problems. The first of these issues was that the growing amount of literate poor that could not afford the expensive books that were being produced. The reason why these books were so expensive was because of a high production cost and the amount of labor necessary to make it all work. To combat this issue, the steam powered rotary printing press, invented in 1843, reduced cost and efficiently brought material to the masses. Cheaper books, such as “Penny Dreadfuls,” were now able to be produced on a massive scale. These publications were not high quality, but they only cost a penny, making them easily accessible to those who could not otherwise afford to read. To further lower costs, the Linotype machine was invented, which revolutionized typesetting and reduced labor.

As publications continued on a massive scale, the issue of copyright came into play. Previously, competition was very low, and a book published in Paris would not likely sell fewer copies if it was reproduced and sold in another part of France. But as travel and distribution of materials improved along with a greater demand for good literature, the concerns about who owned what and who could profit off it became real. Copyright laws took this competition between publishers and regulated it. Publishers couldn’t simply reproduce material that already existed anymore, and publishers and readers alike required more original works.

The same goes for variety in magazines. As audiences grew and diversified, publications needed to meet their needs. In the middle of the twentieth century, a boom in magazines occurred. Specifically between the years of 1925 and 1967, magazines such as Newsweek, Esquire, Rolling Stone, and Seventeen were created and really took off. The fact that these magazines still exist today prove their strength, despite the current major transition to more web-based content.

This online content, which is really where all this publishing innovation has led us to, makes it easier for anyone to self-publish their ideas, art, books, and whatever else they so choose. In 2011, Amazon’s e-book sales surpassed print book sales for the first time, and newspapers and magazines typically have either online editions or are exclusively online. The issue today, which closely mirrors the issue throughout the entire history of publishing, is finding the balance between quality and quantity. As publications move toward online editions, the quality tends to decline even though much more content is produced, similarly to how Penny Dreadfuls allowed for a much wider readership at the expense of high-quality books. As we move forward, it is important to consider the painstaking work and innovation that led us here, and make sure we consider quality despite the ever-growing urge to produce more and more and more.