James Patterson and the State of Fiction

Christina Bagni // Blog Writer

Stephen King, who sees himself as “the literary equivalent of a Big Mac and fries,” once called James Patterson “a terrible writer, but very successful.”

Now, it’s fine to eat junk food and it’s fine to read campy “commercial” fiction like Patterson writes, but it’s hard not to get annoyed at all the inconsistencies in his books. In Patterson’s fiction, characters appear and disappear at random. Personalities, physical features, and ages change book to book. Characters take jobs they swore they never would the book prior, develop super powers that are later forgotten, and on occasion go on book-long tirades about global warming…only to forget about it for the rest of the series. It’s almost as if James Patterson doesn’t care about the details, or at least doesn’t expect his readers to care.

Well…he doesn’t. Let me explain.

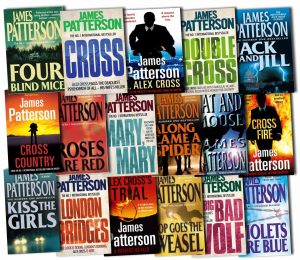

Patterson is the author (or co-author…or has slapped his name on the cover as if he was the author) of a whopping 156 books to date, all published within the last 40 years. That’s 3.9 books a year on average.

At the beginning, he wrote one book every year or so, with a few longer breaks, like a normal person. In fact, he only published

ten books in his first 19 years, from “The Thomas Berryman Number” in 1976 to “Kiss the Girls” in 1995.

1996 was when the strangeness began. He published three books in ’96, and hasn’t skipped a year since. In 2014, according to Jamespattersonbooklist.com, he published 17 books. Seventeen books, in one year.

The Telegraph interviewed Patterson about this in 2014, pointing out that at the time it had been 14,185 days since his first publication, since which he has published 45,651 pages. The article said that “since 2002, just 20 percent of his novels have been entirely written by him.”

The other 80 percent? As you probably know, James Patterson is infamous for using coauthors.

Basically, he gives various coauthors outlines and they write a few chapters at a time, with him heavily editing as they go. It’s a symbiotic relationship—Patterson gets books written, and the authors get an instant bestseller to put on their resume as well as royalties and usually their own book deal.

Mark Sullivan, who co-authored 2012’s “Private Berlin” with Patterson, said that it was like a “crash course” in writing commercial fiction. He was told by Patterson that above all else, the book had to hold the attention of busy readers.

This explains Patterson’s oft-critiqued super-short paragraphs, sometimes only half a page long. It also explains his lack of care for inaccuracies—he’s not writing for super fans who would notice that someone’s hair color changes from brown with blonde streaks to strawberry blonde to black book to book, or who would roll their eyes at a character’s second or third resurrection/cloning. He’s writing for the busy parent who’s reading while waiting for soccer practice to be over, or for people to read on the subway, or while cooking. A big advocate for keeping reading relevant, Patterson realized adapting to this fast-paced, instant-gratification century was more successful than writing something more complex and “literary.”

To be frank, he’s not wrong. A constant bestselling author, he certainly makes more money than most authors of high fiction, and certainly publishes more books, even if he only writes two out of every ten words.

Patterson’s newest idea, what he calls “BookShots” but are really just “Short Stories with a Fun Name,” may seem silly but are actually a brilliant remarketing of short fiction, the kind of fiction that would probably appeal more to today’s audience if they weren’t intimidated by the supposed difficulty of fiction. Patterson’s theory is that if you don’t have time for a long novel and don’t have the energy to pick apart challenging stories, it’s at least good to be reading something.

If you disagree, keep in mind that 27 per cent of American adults said they hadn’t read even one book in all of 2015.

As a Writing, Literature, and Publishing major and a lover of challenging fiction, Patterson used to infuriate me. Now that I see his reasoning, I am more understanding, but he reminds me of a band that changed their signature sound to get more fans. It’s the common question of passionate versus successful—though, perhaps Patterson is one of the lucky few to be both.

Patterson is for people who read casually and don’t have the time or energy to read something “literary.” Like Steven King said, he’s “terrible, but very popular.” Coming from the Big Mac himself, that’s a pretty big compliment.

Love him or hate him Patterson has found a way to remain successful and relevant after all these years. He might not be for the “literary” folks but clearly there are plenty of people who enjoy his approach!