Meaghan O’Brien // Blog Writer

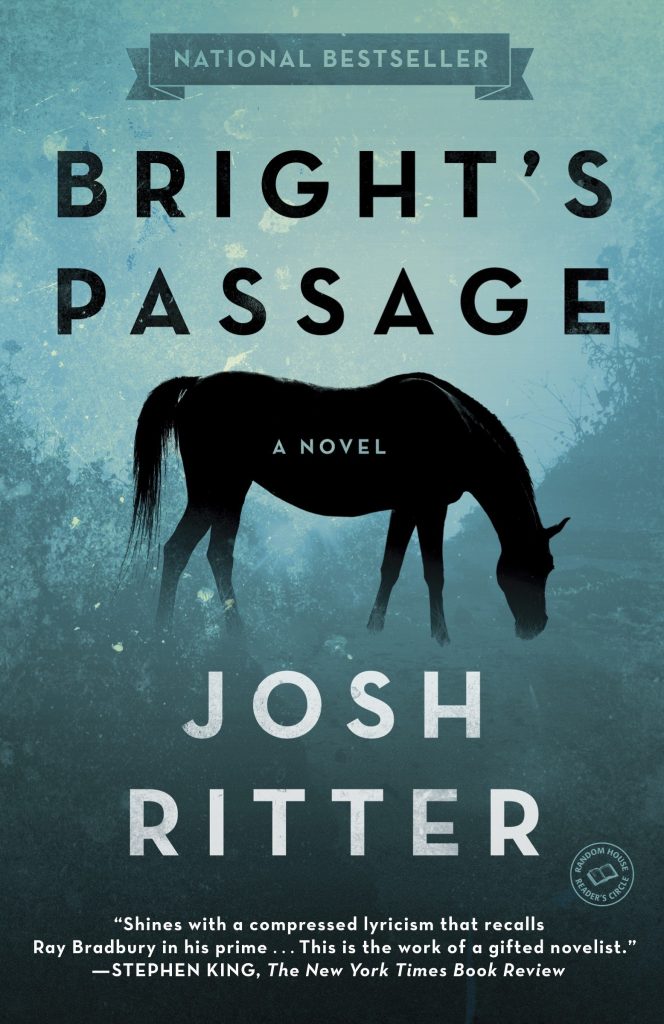

I’d call Josh Ritter a storyteller. I think he’d call himself a storyteller, too. He’s known and acclaimed for his singer-songwriter folk with a prosaic bent and, more recently, for his debut novel, Bright’s Passage. Josh has garnered much praise for his songwriting, considered by some to rank among the likes of Bob Dylan. His success lies in his storytelling abilities through music, his well-crafted lyrics, and the emotion in his songs. In one song, “The Temptation of Adam”, the narrator Adam , an operator for an underground missile operation tells the story of he and Marie, another operator, their love affair, and his fear for their love when they return to reality. Another, “The Curse”, tells the story of an Egyptian mummy, exhumed and brought to New York by an archaeologist with whom the mummy falls in love. But because he was taken from his tomb, the curse that he carries with him eventually kills the woman he loves. And then he has lines of poetry like these from “Southern Pacifica”: “Climb through the timbers/ And I’ll breathe the dust/Of cosmos and wild rose bud/ And thunder the unknowns/ In the phosphorous white glow/ Of saber-tooth bones in the dusk.” Both his stories and his lyrics are compelling.

But then there’s the music itself. “Temptation of Adam” would never be as endearing as it is without the tremulous horns and quivering strings that are featured throughout. The main accompaniment in The Curse is a waltzing piano that, with its crescendos and diminuendos creates a dreamlike quality to the song. I’m not trying to discredit Ritter’s abilities as a lyricist or to say that his narratives are dependent upon the music that accompanies them to work. The music, rather, enhances the story; it speaks to something more primal in the listener and tells the story in ways that words can’t. Literature has the same impact, but clearly achieves it differently. The words become much more important because they are all the storyteller has to go on. So, in considering Bright’s Passage before reading, one of my biggest sources of skepticism was simply this: without the help of major or minor chords, lilting strings or finger-picked guitar, would his words have the same weight? And yes, despite his success as a songwriter, I was skeptical. Being good at one art form does not guarantee success in another.

Curiously enough, Bright’s Passage began as a song. The story’s life as a song was short-lived; however, as after several attempts Ritter scrapped all attempts. But he found he had a lot to say about Henry Bright, more than could be said in a span of 3 or 4 minutes. So, Ritter sat down to write 1000 words a day for fifty days (his work ethic is enviable), and had himself a first draft. He spent 7 months editing the story into the novel in its present state. Bright’s Passage tells the story of WWI veteran Henry Bright and what befalls him when he heeds the demands of an angel. After Bright’s wife, Rachel, dies in childbirth, Bright burns his home at the urging of the angel (who speaks to him primarily through his horse) and flees with his son to escape the fire and Rachel’s father, the Colonel. It was at the angel’s urging that Henry stole Rachel away from her home to marry her, and the Colonel, along with his two dolt sons, pursue Bright and the baby to exact their revenge. Along Bright’s journey, his past both in West Virginia and in World War I are told through a series of flashbacks. Henry first came into contact with the angel during the War in a church in France, where the angel saved him and promised to make his son the Future King of Heaven. As Bright makes his journey and adjusts to having a baby, the threat of the fire and the Colonel’s revenge looms very close behind him.

The most important similarity between his music and his literature is that they focus on the same themes. War is a reoccurring theme; some of his song characters are soldiers or discuss war, as in “The Temptation of Adam” or “Girl in The War”. Religious allusions are frequent in his music. Male characters in pursuit of ideals are also recurrent; songs such as “Next to the Last Romantic” and “Another New World” feature such characters. And of course, love is nearly omnipresent. Also, many of the songs feature characters that possess some kind of folk history or Americana. Even an untrustworthy angel is featured in one of Ritter’s songs, “Galahad” (to be discussed at length shortly).

In an interview with PBS News Hour about Bright’s Passage, Josh commented about the writing process; “I began to see how much like songwriting it is. Everything single word is so important…” His meticulousness is evident in his songwriting; there never seems to be a word out of place. And it’s evident that this was process was for Bright’s Passage as well, though unfortunately with less success, because it resulted in the sentences being overwrought. Though there definitely some beautifully crafted lines within the story, much of the narrative was rather clumsy and laden down by excessive adverb use. Though, I must give credit where it’s due; I did learn from him a number of odd adverbs such as “jollily”, which I had no idea existed. For much of the book, I had the strongly sneaking suspicion he kept a thesaurus open next to him as he wrote. Josh’s stories in his songs are so great, but one of the reasons for their success is the simplicity of the lyrics and the directness and the emotion imbued through that simplicity. Had he stayed more true to his previous work and emulated the style of his lyrics, Bright’s Passage would have read better.

One of Ritter’s strengths that is equal between the two mediums is the strength of the voice of his characters. From song to song and also within the novel, the characters have very distinct voices. As a reader, the characters in Bright’s Passage did live and breathe. That is, all but one; the angel was not utilized as much as it could have been. Ever the Fight Club enthusiast, I wanted the angel to have a touch of Tyler Durden’s mischief, though it seemed to be more of an annoyance than anything else. Bright voiced his frustration frequently in his conversations with the angel, nearly always followed the same pattern. This failed to really develop the angel as a character. The only things the angel threatened Henry with were the death of his son and the prospect that the boy would never become the Future King of Heaven. While these proved effective throughout much of the story, given the broad spectrum of what an angel would be able to use and manipulate, the angel came across as rather benign, and increasingly so throughout the novel. What I was actually expecting was something similar to another character, the Angel of the Holy Grail, that figures in Ritter’s song “Galahad”. In the song Sir Galahad finds the Holy Grail, which is guarded by an angel with its own agenda. The angel praises Galahad and offers him to drink of the grail, but first he warns him that the sins Galahad enjoys on earth will not be there in Heaven. Filled with guilt, Galahad jumps at the opportunity for Heaven, doffs his clothes as the angel instructs, drinks from the Grail, and dies. The angel doesn’t bring Galahad to Heaven, but instead dons his armor and heads off for Camelot to reap the glories of having discovered the Grail. If Bright’s angel had had the great selfishness that the Angel of the Holy Grail did, he would have lived up to its potential as a character and a driving force in the novel.

And so, after a rather lengthy explanation, we come to the heart of the matter: in which kind of storytelling was Ritter more successful? If it’s not already evident, I definitely believe that his songwriting is the more successful storytelling medium for now. His lyrics include narratives with solid arcs, beautiful words, and great music. The novel shared some of the characteristics of his music, but it just didn’t sing. However, I don’t think this should be his only novel. He is a talented storyteller and if he looks to his own body of work, I think he’ll find his strengths and grow as a novelist. To do him credit, I did spend some time reading customer reviews of the book and while many people share my opinions, many others genuinely loved it. As it stands, the book was really moving for a lot of people and shouldn’t be pushed aside. If you don’t read the book, listen to his music. Support a storyteller. As Neil Gaiman once wrote, “The important thing about songs is that they’re just like stories. They don’t mean a damn unless there’s people listenin’ to them.”

Playlist of Suggested Listening for Josh Ritter (both mentioned above and otherwise)

o The Temptation of Adam ( Album: The Historical Conquests of Josh Ritter)

o Galahad (To The Yet Unknowing World)

o The Curse (So Runs The World Away)

o Another New World (So Runs the World Away)

o Folk Bloodbath (So Runs the World Away)

o Girl in the War (The Animal Years)

o Next to the Last Romantic (The Historical Conquests of Josh Ritter)

o Monster Ballads (The Animal Years)

o Come and Find Me (Golden Age of Radio)

o Harrisburg (Golden Age of Radio)

o Kathleen (Hello, Starling)

o California (Hello, Starling)

o Bright Smile (Hello, Starling)

o Chang of Time (So Runs the World Away)

o Can’t Go to Sleep (Without You) (Bring on the Darlings)