The Risks of Publishing

Victoria Kiarsis // Blog Writer

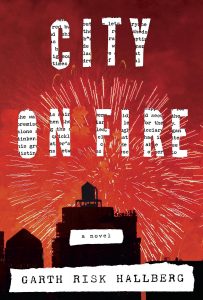

City on Fire was released in October of 2015—you’ve probably heard of it, but you probably haven’t read it. In one year Garth Risk Hallberg’s book—his middle name incredibly ironic—has sold only 65,000 hardcover copies, yet the publishing house, Knopf, paid 2 million dollars for the manuscript. In order to break even on that sort of payment, there would need to be—to my rough calculation—at least 350,000 hardcover copies sold. The Wall Street Journal calculated 75,000 hardcovers, 75,000 paperbacks, and 150,000 ebooks, adding up to 300,000 copies. In a year it has barely earned back twenty percent of the money the publishing house spent on this risk. And that’s exactly what every publishing house does when it buys someone’s baby. It takes a risk. Yet Knopf seems “unconcerned,” wrote Stuart Emmrich in a New York Times article, and added that “this is a book [Knopf] expect[s] people will be reading in 20 years.”

What happens to Knopf when or even before they’ve admitted, if they do at all, that City on Fire was a failure?

First come the returns. The return of unsold books is actually a normal occurrence and is taken into account when publishers map out how much money they’ll be spending to produce and sell a book and how much profit they will make. Usually returns will be around twenty to thirty percent of the gross units sold to places such as brick and mortar bookstores. Perhaps the brick and mortar stores think that the book will sell still after the three or fourth month period of time when returns begin coming in, but surely after a year of slow sales, this book will disappear in a big way from the aisles. Eventually these unsold books go through the process of “pulping,” which is essentially the recycling of the paper, as a way to make some money back.

Another way that a publisher can recover the money the hardcover edition lost is by bringing out a paperback edition of the title and really working up a major marketing blitz with good review blurbs, wide advertising, and word-of-mouth buzz. This often works—although the paperback of City on Fire was released around six months after the hardcover and the numbers weren’t impacted greatly. Knopf wrote National Bestseller on the top, yet the average rating of the book on Barnes and Noble’s website was a 2.9 out of 5.

But how can a publishing house even survive after this substantial loss? Well, the fact is that they do—and it’s because of the 20 percent of authors that actually do sell millions of copies and cover the costs of these “promising” debut authors who very rarely make money for a publishing house. For Knopf it could be Helen Fielding, the woman who wrote Bridget Jones’s Diary. It could also be that Knopf was acquired by Random House in 1960, which in 2012 merged with Penguin—therefore the two combined have billions of dollars in annual revenue. Clearly enough to take a 2 million dollar risk on Garth Risk. I imagine it to be like if you got arrested and put in jail for the night because of something stupid you did with your friends and your parents came to bail you out. What doesn’t happen though, is little publishing houses taking such huge chances. They simply can’t. Publishers are well-versed in the language of risks, as the entire business is built off gambles. If the money is not there, it won’t be offered. And sometimes that’s okay.

David Hirshey, who is the senior VP and executive editor of HarperCollins, had a 1 million dollar contract with Amy Schumer for her collection of essays. In 2014 Schumer cancelled the contract, yet the next year—after her win of an Emmy and the release of her successful film—she had a new 9 million dollar contract with Simon and Schuster. Hirshey responded that he was not upset, but that he was “thrilled to cost one of our competitors $9 million.” And perhaps they will make that money back like Little, Brown and Company did when they gave Tina Fey 6 million for her book Bossypants. The difference from City on Fire is that these celebrities don’t need good reviews or even a ton of ads—they already have followers. Hallberg was a professor at Sarah Lawrence College and his reviews didn’t even yield the best of the best.

So to sum it up—big publishing houses can take massive million dollar risks because they have millions of dollars to spare. Whatever happens with the copies sold, it seems you have to be rich or famous in order to publish a book that you don’t really know is going to make back the money you spent on it. If you have never been published before, maybe accept the five thousand dollars they’re offering and then hopefully one day someone will risk a million or more on you too.