Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, and so Does Oates

Kyle Labe//Blog Writer

Decades after her untimely death, Marilyn Monroe remains an archetype in America’s collective unconscious. Like Hollywood’s version of Helen of Troy, Monroe’s beauty has transcended time, and images of her white skirt flying up on a subway grate, or her sultrily singing to President John F. Kennedy, or her ukulele-playing screwball comedy in Some Like It Hot have passed from generation to generation. Why is that so? What is it about Monroe’s being that still, to this day, enamors all who see her? Joyce Carol Oates tries to figure that out in Blonde, her 2001 fictional biography detailing the actress’s life from childhood to death.

Blonde is a peculiar read. If you have never read Oates before, it’s a wild ride. Luckily I’m familiar with the author, and because of that, immediately recognized that the novel is Oates in all her postmodern, Gothic glory. At times, the prose is convoluted, stream-of-conscious, switching from points of view like blinking an eye. She maintains this symbol of a Beggar Maid and a Dark Prince, and by the time you finish the book, you understand this about as much as you did entering it. Sometimes the story slugs on, especially in the middle of the book, as will happen in a 700-plus-page book.

All things considered, this book is an epic feat in literary fiction. Monroe comes alive on the page as Norma Jeane Baker—the actress’s given name—while also taking on personas of the Blonde Actress, the Gemini, Miss Golden Dreams, and each of her film’s characters. Through time, so many rumors and so many lies have been smeared on Monroe’s legacy that her real self is constantly overshadowed. When exploring Monroe’s biography, it’s vital to see her not as some Hollywood sexpot, but as an ambitious, intelligent young woman determined to create art, who struggled with mental illness and abuse from the men around her. She was not the “dumb blonde” character she played on screen—that’s why it’s called acting. And Oates knows this, much to the novel’s benefit. Blonde is a personal and political triumph, and I encourage anyone unfamiliar (or familiar) with the feminist movement to give this book a read. In a way, this is Oates reclaiming Monroe’s legacy, not as her reputation, but for what she really was.

One particularly intriguing aspect of the novel is the mother-daughter relationship of Monroe and Gladys Baker. A woman struggling with severe mental illness, Gladys tries raising Monroe as a single mother, and the novel presents a woman so raw and ugly in its realness, that in her many flaws, is refreshing to see a motherly character as such. Very seldom is a secondary character written so intricately. And it’s the same with many of the other characters: from Cass Chaplin Jr., to her first husband (written as “Bucky Glazer”), to Joe DiMaggio (written as “the Ex-Athlete”), to Arthur Miller (written as “the Playwright”), to the various employees at the Studio.

However, the story centers itself around Monroe, and Monroe is the character to which we should be most enthralled. This is the part of the book that boggled with my mind the most. From reading about such complicated and honest secondary characters, I expected the protagonist to be much of the same. Yet that is not what I found. Monroe seems to be the entire work, yet none of it, filling both the whole world and not a tiny speck in it concurrently. Sometimes she’s a tangible portrayal of a young career woman, though at other times it feels as if she’s barely present. I kept wanting more from her. I understand this is where the troubles with a fictional biography come in. The author can never truly enter the mind of its protagonist, and maybe that’s the point in Oates’s writing. There are so many assumptions, speculations, and theories that have to go into it, that maybe you can’t conjure the person’s image, regardless of how hard you try.

Additionally, this is also where many of my complaints fall. At times, Oates writes with a sensationalist tilt, tiptoeing into the land of conspiracy theory. I won’t spoil the end, but I will say that it’s a huge disappointment, and she finds herself not taking simple, hard fact and exploring the grounds of conspiracy, which plays a huge role in the false reputation of Monroe that Oates attempts to dissect. It erases Monroe’s mental illness, almost trivializing it, and Oates is guilty of infantilizing Monroe at points. You see flickers of Monroe, but Oates finds a way to dismantle it. Albeit Oates penned a forward detailing that one shouldn’t read Blonde for biographical, factual information on the star, it’s hard not to when it’s marketed and written as such.

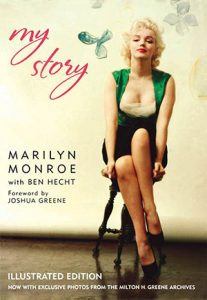

Blonde is in a strange place where I recommend it wholeheartedly, but doubt if I will read it again. If anyone is interested in Monroe, I suggest reading her autobiography, My Story, or the even more intriguing Fragments, which includes her poetry, journals, and personal writings. One will be surprised at the insights and talent of the actress, who had a particular knack for poetry. That’s where the true Monroe can be found—in her own voice.