Where History Begins

Andi Smith // Blog Writer

I’ll ask you a question that seems simple: what is historical fiction?

That’s not a trick question: it’s just fiction set in a historical moment.

It is, however, a bit of a trick answer.

According to my American History professor, history ends with this semester: we’ll learn up until whatever time period the schedule allows. History continues up until the very moment I write this. I’ve had the thought myself: isn’t all fiction technically historical, because someone wrote it in a time before the present?

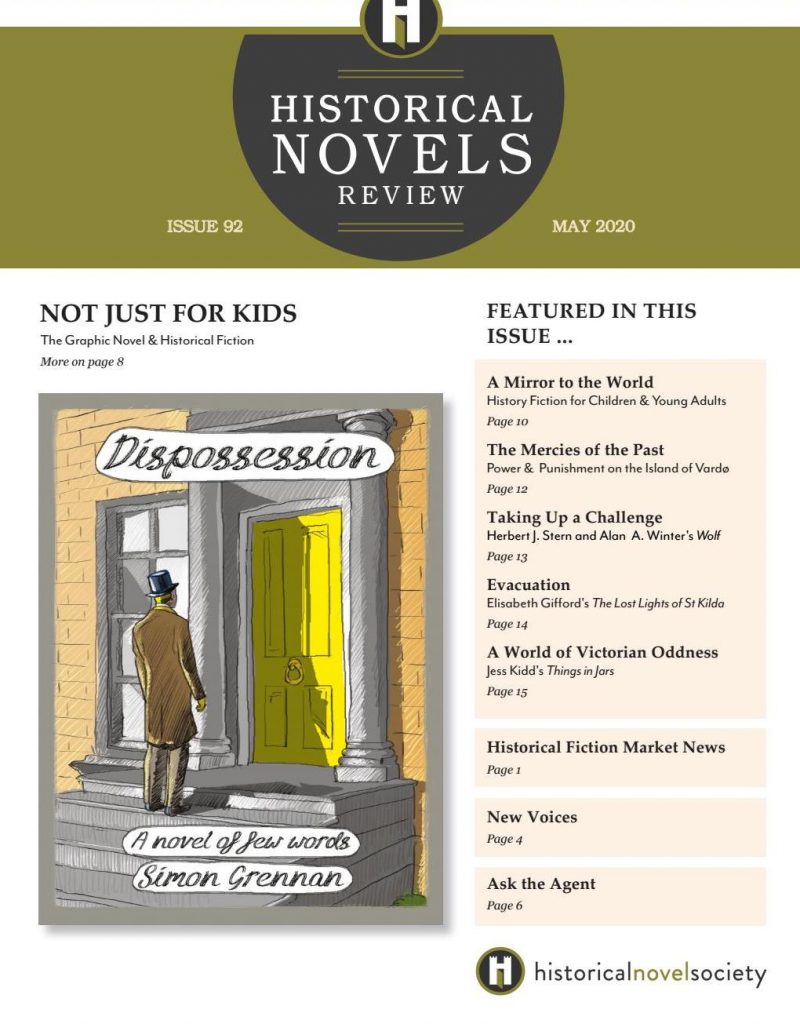

Not according to the publishing industry. One database, Historical Novels, ends its list in the decade after World War II. In the Historical Novel Society’s database of book reviews, none represent the twenty-first century. Wikipedia goes to 1990 with the book Prague, by Arthur Phillips, set during the end of the Cold War in Hungary. Another book, The Forgotten Daughter by Joanna Goodman, sets part of its story in the same decade. Even the then-recent events are woven in with the stories of years gone by; many historical novels have a modern frame, where older characters recount their past, but are still marketed as historical fiction.

Such a designation might be based on the lack of personal experience. According to Sarah Johnson, review editor for the Historical Novels Review, historical fiction is set at least fifty years before its publication and is something the author had to research beyond personal experience. Historical fiction is something separate from our own time, even if history can feel quite recent. If this definition is true, then an older Hungarian writing a novel about the end of the Cold War would be writing fiction, while a twenty-year-old Hungarian writing the exact same novel would be writing historical fiction. The novel is both historical and independent of the context of the author, who is outside of the narrative.

That feels a bit too Schrödinger-y to me. And anyway, why does the author need to matter that much to the text? For any other literary genre, we look at the text itself, rather than who wrote it.

Perhaps the time does not matter so much as the time period. Writing a book set in 1990 Hungary about the effects of the Cold War would be a very different novel from a coming-of-age set in 1990 rural America; the latter would not find much of its relevance in grand historical moments, as coming-of-age stories tend to be much more timeless. I think of it like this: if you can write a book where the fictional events are more influential to the plot than the historical events, then it’s probably not historical fiction. A very loose definition, sure, but one that accounts for more variation than the fifty-year rule.

Of course, there’s nuance to be considered. Sometimes, events feel too recent to be historical because they are currently changing our social thought. The 2016 election, for example, is not necessarily a historically fictitious subject because the effects are still visible in our culture. If I were to write a novel about the aftermath of 9/11, it would be much more historical for me because I don’t remember it; someone who vividly remembers the event might think of it as regular fiction.

If an event did not change one’s perception of society as it occurred but still shaped the world they lived in, then to them, it is historical; if they can remember before the impact of the event, then it isn’t historical. I grew up in the aftermath of 9/11, while my parents had to adjust to the new world it created; but during the 2016 election, I had to actively change my view of society. This is another Schrödinger situation, but one which focuses on the reader instead of the author. Whether or not something is historical fiction is still conditional, but conditional on the part of the reader instead. For me, certain books feel historical, and there aren’t enough books in the gray area to necessitate intense debating. Maybe it depends on everyone together—who’s reading, writing, publishing, or marketing it—but hopefully, that will be us one day.