#OwnVoices and the Conditionality of Representation

Emma Shacochis // Blog Director

When we discuss diversity in publishing, as important as it is to look at the internal operations of publishing houses, we also have to look at what – and who – these houses are choosing to publishing.

#ownvoices, to recommend kidlit about diverse characters written by authors from that same diverse group.

— Corinne Duyvis | buy THE ART OF SAVING THE WORLD! (@corinneduyvis) September 6, 2015

#OwnVoices began in 2015, conceived by author Corinne Duyvis. In its simplest definition, #OwnVoices is a term used to indicate when authors write from personal experience stemming from being part of a marginalized group. Duyvis’s novels, from Otherbound to On the Edge of Gone, include mains who are autistic, disabled, and bisexual – just like their author. (On the Edge of Gone was, as of 2016, only the third novel to feature an explicitly autistic main character written by an autistic author.)

Duyvis has repeatedly spoken about why she began the #OwnVoices hashtag, as well as her longtime intentions for how it would turn out. “It was frustrating to see people occasionally shove aside the need for more diverse authors. If you only show marginalized experiences as filtered through the eyes of people who aren’t marginalized themselves, you end up with a skewed perspective, no matter how well-intentioned the authors are or how much research they do,” she said in a 2016 interview, adding that, “These people exist. It’s not about ticking boxes; it’s about showing reality. I am not a deviation from the norm. I am the norm in my own life…Marginalized authors need to have the same opportunities, the same support, and the same freedom as everyone else; we can’t demand diversity if it’s only on certain terms.” The term was intended to apply to any kind of identities, “as long as the protagonist and the author share a marginalized identity.” On her personal website, Duyvis clarifies that, “A book being able to ‘claim’ the #ownvoices label does not place it or its author above criticism. It’s not an automatic seal of approval.” Recognizing a book by an #OwnVoices author isn’t an indicator of its quality – it’s only meant to alert interested readers to the type of protagonist being represented by the author. Duyvis is also adamant that #OwnVoices doesn’t insist that any author can only write about their own identity (marginalized or otherwise): “It’s about looking at the diverse books we have or are calling for, and consciously prioritizing those from authors who can speak from their own experiences.”

These people exist. It’s not about ticking boxes; it’s about showing reality.

What began as a tool for book recommendations has, in 2020, “become an integral part of the publishing lexicon: it’s used in deal announcements, manuscript wishlists, query pitches, trade reviews, thinkpiece headlines, and countless important conversations about representation of marginalized groups in different media,” according to Duyvis. She’s witnessed the benefits of the shorthand: “I’ve seen lots of marginalized authors feel emboldened by the popularity of the hashtag, saying it gave them the faith that people actually wanted to read the kind of novels they hoped to write…Readers have a much easier time finding books with respectful, accurate, nuanced representation.”

The state of such representation can be bleak: in 2019, the Cooperative Children’s Book Center reported that only 49% of U.S.-printed children’s books about Black or African main characters were written by Black or African authors. While books about characters of any identity are not meant to represent the experience of every member of that group, it is still meaningful for those readers to witness authentic and varied representations of their lives. If Black authors are not being given the same chances as white authors to tell their own stories, there is a greater chance that these portrayals will come across as false or even offensive. On top of this, there’s the fact that children’s book publishing has a severe weak spot when it comes to diversity: in 2018, only 10% of the main characters in young readers’ books were Black (there was a greater chance that you would read a book about an animal lead than one of Asian descent).

#OwnVoices has brought attention to the works of marginalized authors depicting their own identities. It was created with good intentions, and has been used by numerous authors who fit into We Need Diverse Books’s definition of “diversity.” But lately, the resistance toward #OwnVoices has become more verbalized. Duyvis herself has been aware of the tag’s weaknesses, pointing out that it has led to, “excessive identity policing and pressuring of marginalized authors that we’ve been seeing.” Author Dahlia Adler, creator of the LGBTQ Reads Blog, wrote in a post that, “I think there’s something extremely problematic about making readers dig into authors’ sexualities. And I get wanting to support #ownvoices – obviously I do – but as someone on the author side, I’m seeing it cause a lot of harm among authors who can’t come out but now feel they have to.” Authors who are personally private or closeted but writing about LGBTQ main characters may feel they have a responsibility to come out about every specific facet of their identity, so their books can receive the #OwnVoices label and serve as responsible, correct diversity for readers of the same identity. This seemingly-forcible aspect of the tag may alienate authors from wanting to participate in it at all; alternatively, it may encourage certain authors to become sudden members of marginalized groups. Jeanine Cummins, author of the controversial novel American Dirt, “as recently as 2016…identified as ‘white.’ In the lead-up to American Dirt’s release, Cummins revealed she has a Puerto Rican grandmother.” It would appear that, to escape the criticism sometimes leveled at white writers who depict marginalized groups, Cummins chose to reveal an aspect of her heritage to act as a shield against criticism. So should #OwnVoices celebrate her for having Hispanic heritage and writing about Mexican characters? Or can marginalized groups be rightfully upset that diversity is being used as an excuse for poor, offensive representation?

As someone on the author side, I’m seeing it cause a lot of harm among authors who can’t come out but now feel they have to.

Author Sarah Raughley has also revealed long-term issues with the hashtag, especially once it reaches the currently barely-diverse publishing houses: “I can imagine folks at a meeting going, ‘Angie Thomas made YA books about Black people acceptable to children’s publishing! Alright, now we’ll only publish Black contemporary authors who write about police brutality, incarceration, and other social justice issues!’ On the fantasy front, publishers seeking work from writers of African backgrounds only wanted to see Afrocentric fantasy novels that perfectly encapsulated the writer’s African culture, which they must be 100 per cent connected with and knowledgeable about. The writing had to possess what white publishers viewed as authentic Blackness.” As Raughley explains, there are now standards for the “right kinds” of diversity: the #OwnVoices authors who succeed are then made into examples for the only types of marginalized stories that need to be told from that group of writers.

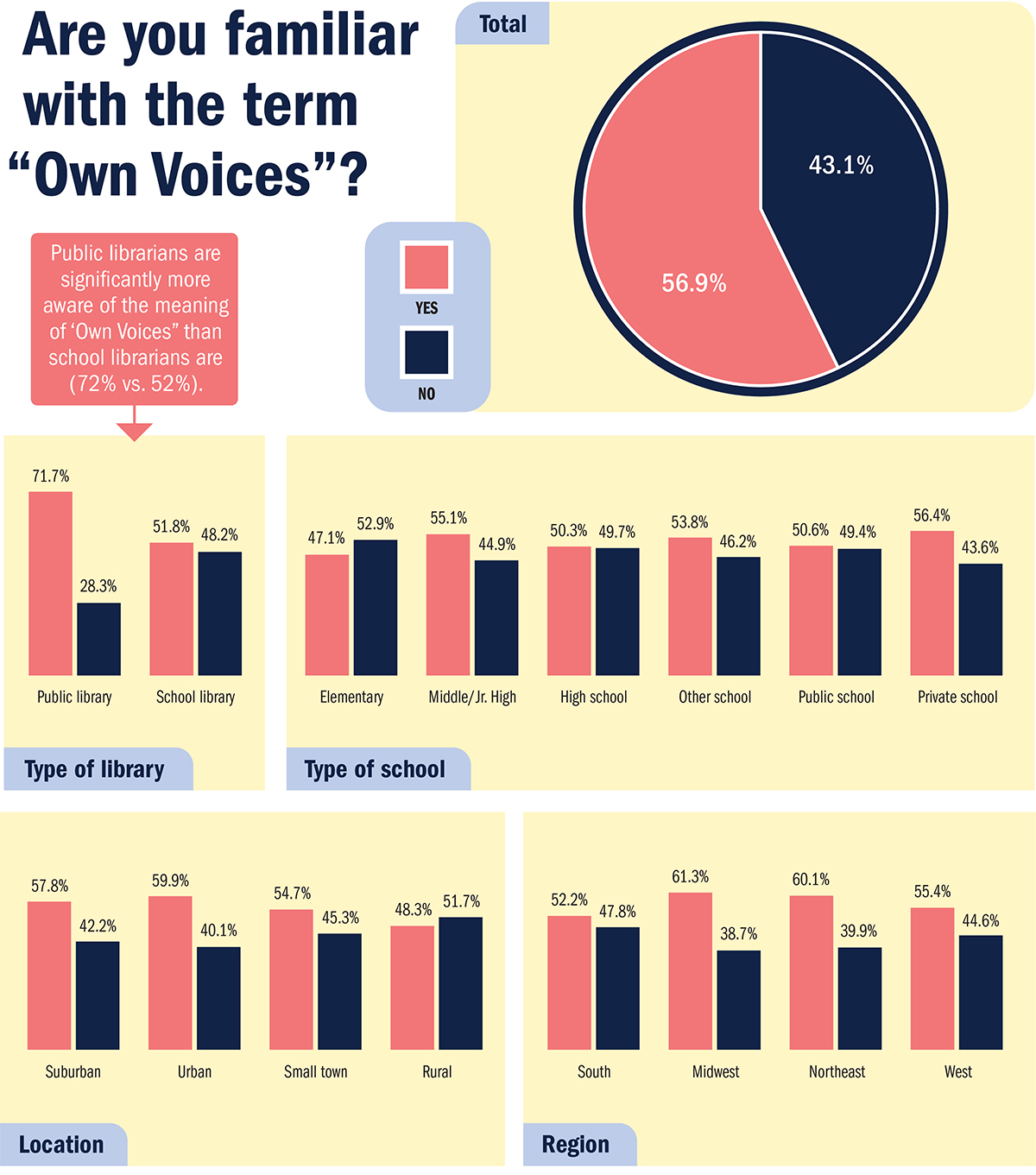

As shown above, #OwnVoices is a term on the rise – while numbers are close, the majority of librarians have become aware of its meaning as of 2018. While it continues to grow in popularity – and in the cases of libraries, this seems like a definite benefit when it comes to the types of books children will be exposed to at younger ages – it becomes more vulnerable to fair criticism. In 2021, We Need Diverse Books announced that they would stop using the term to refer to literature and authors, choosing instead to refer to diversity in books with “specific descriptions that authors use for themselves and their characters whenever possible.” This switch to personalized labels comes as a rejection of the way #OwnVoices “has since expanded in its use to become a ‘catch all’ marketing term by the publishing industry.” Like Adler and Raughley worried, #OwnVoices is no longer just a victory for the authors able to represent their own stories, but an oversimplification of what diversity means to publishers. With the knowledge of Duyvis’s intention for the hashtag, this becomes a bittersweet announcement, but an understandable one. We should hope, though, that changes within the publishing industry can lead to #OwnVoices being a celebration for its authors and audiences once more. As author Amanda Kabak puts it, “It requires diversity within the ranks of people in power—the gatekeepers, the tastemakers. It requires us all to try hard to put ourselves into other people’s shoes and challenge ourselves to deeply understand and empathize with a variety of experiences. Frankly, it requires more (and more delicate and thoughtful) work than I suspect most people want to put in.”

Featured image courtesy of LittleFeminist.