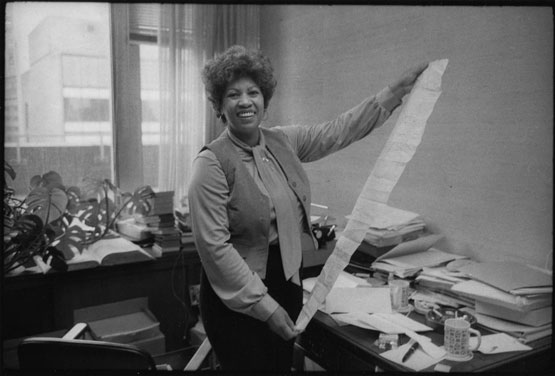

Toni Morrison, Publishing Pioneer: “You Need to Free Somebody Else”

Emma Shacochis // Blog Director

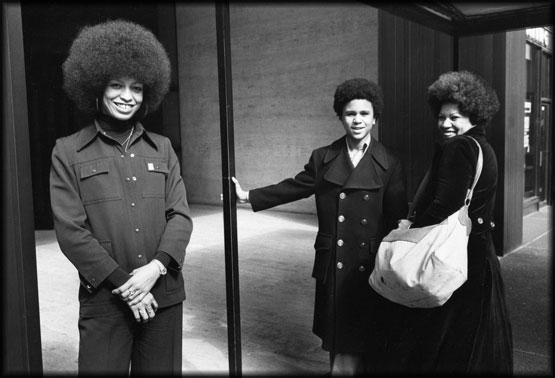

Working for what is now one of the “Big Five” publishing houses in the industry (the company now goes by Penguin Random House), Morrison was responsible for the work of Black female writers including Gayl Jones, Angela Davis, and Toni Cade Bambara being published; she pushed for anthologies like Contemporary African Literature and The Black Book to be printed throughout the 1970s. After the murder of novelist Henry Dumas, Morrison not only published his works, but worked to properly publicize them and his life. In cases like this, or when Morrison published Muhammad Ali’s The Greatest, Random House employees and bookstores were skittish about being part of the promotion. Morrison would take matters into her own hands, sending copies of the books to influential members of the entertainment industry and pushing for launch parties to be held in Harlem despite wariness from marketing associates. She didn’t solely publish the work of activists, but didn’t resist showing support of Black Panther writers and members of the Nation of Islam.

It was her goal, in an industry that reduced the presence of Black readers and writers, to work on publishing at least one manuscript from an African-American author per season, saying, “I wanted to give back something. I wasn’t marching. I didn’t go to anything. I didn’t join anything. But I could make sure there was a published record of those who did march and did put themselves on the line.” She hoped to choose books that represented the widely-varied perspectives of the Black American experience. It would often pay off, critically and financially, for the publishing house – a review of The Black Book wrote, “Editors, like novelists, have brain children – books they think up and bring to life without putting their own names on the title page. Mrs. Morrison has one of these in the stores now, and magazines and newsletters in the publishing trade are ecstatic, saying it will go like hotcakes.”

Still, Morrison did not feel as though she was working in the industry always meant for her. “They didn’t hire me to be one of them,” she clarified when asked why she never told her fellow employees at Random House that she was a writer. Morrison applied for the position because she needed a job, and when she learned the power she held, she used it to diversify the literature being represented by the company. As a woman, she was “never paid a living wage” for her work, and often faced extra doubt from publishers about some of the manuscripts she chose. While she later chose to become solely a novelist, Morrison’s impact on the industry at the time was indelible. Her own words, “If you have some power, then your job is to empower somebody else,” are not just advice for a new generation of readers and writers: they reflect on a career spent working to give all voices a well-deserved chance to be heard. So often, who is doing the publishing affects who is being published. Diversity in publishing relies on someone’s devotion to representing a wide range of perspectives through their platform.