The Body: An Obligatory Haunted House

Allison Armijo // Blog Writer

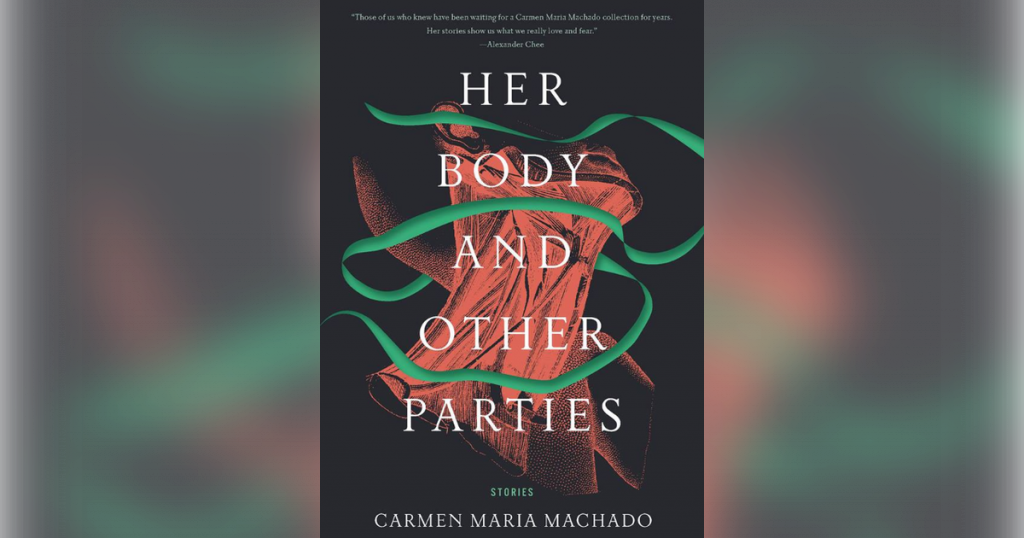

Carmen Maria Machado is no stranger to horror, as a genre, or as an experience. Critically acclaimed author of In the Dream House, a memoir about queer domestic abuse, Machado is known for confronting difficult spaces to deliver a message. Her collection of short stories, Her Body and Other Parties, is no different, as it relays the horrors of a gendered body through a modern feminist lens.

Each of her stories, eight in total, interrogate the idea of power in sex, or more accurately put, power in the body. Ranging from a story of a wife whose neck is held together by a green ribbon that she refuses to let her husband pull, to the ghosts that result from shedding one skin for another by way of bariatric surgery, Machado interrogates the body and the dangers of defiance in a space that thrives in tradition. Each story is biting yet nostalgic, a particularly horrific reimagining of the potentials of a gendered body in a space we all seem to recognize.

While Machado’s stories are not akin to the type of horror that Stephen King writes, they are a harbinger of things we are aware of. What makes her delivery so impactful is that she writes each story like a love letter, using beauty to reveal what lurks beneath the surface. Because of this, a more apt comparison to her work would be to Shirley Jackson, who also manipulates commonplace settings to reflect more sinister machinations of our everyday lives.

Some of the overarching themes of Machado’s stories are those of ownership and obligation dealing with the repercussions of their own autonomy. All the female protagonists are painfully aware of the spaces they occupy, even if they don’t necessarily want to be. For example, in “Real Women Have Bodies,” the protagonist works in a dress shop, soon discovering that the dresses ‘come alive’ when the women behind them fade away.

While all the stories in this collection invoke gothic themes, it is their focus on one’s obligation to the body—both their own and those of the people around them— that generates fear. Each piece has a lingering effect, forcing people to act, and react, to a state of being that they find themselves in; a living, breathing, haunted house, if you will.

Machado does not offer a solution for how to interrogate one’s body. Instead, she magnifies the horrors of living in a gendered body, using macabre elements to communicate the reality of this experience. They are not hopeful, but they do promise a recognition of perfunctory parts of our existence. In this way, Machado’s stories are a painful, but necessary, love letter to our bodies and the bodies of the people around us. She tells us that we are always obligated to ourselves, even if the obligation we feel is to a haunted house.