Reading and Remixing: Teaching the Self-Generating Poem

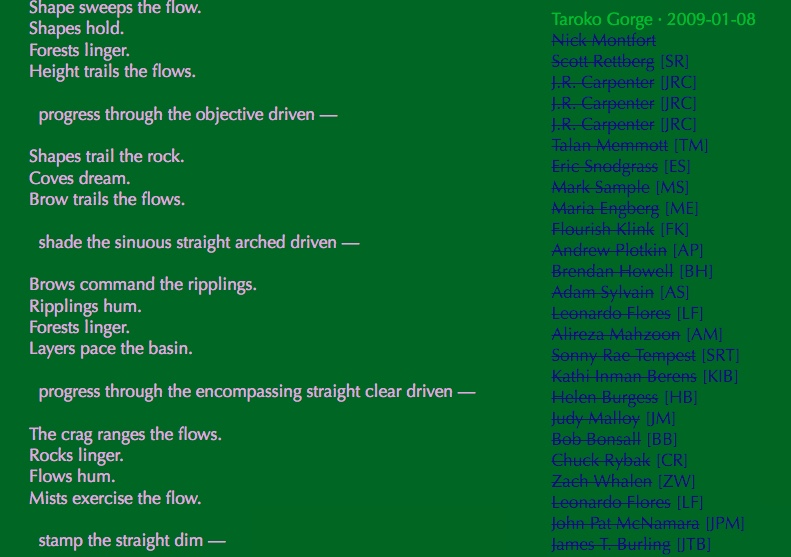

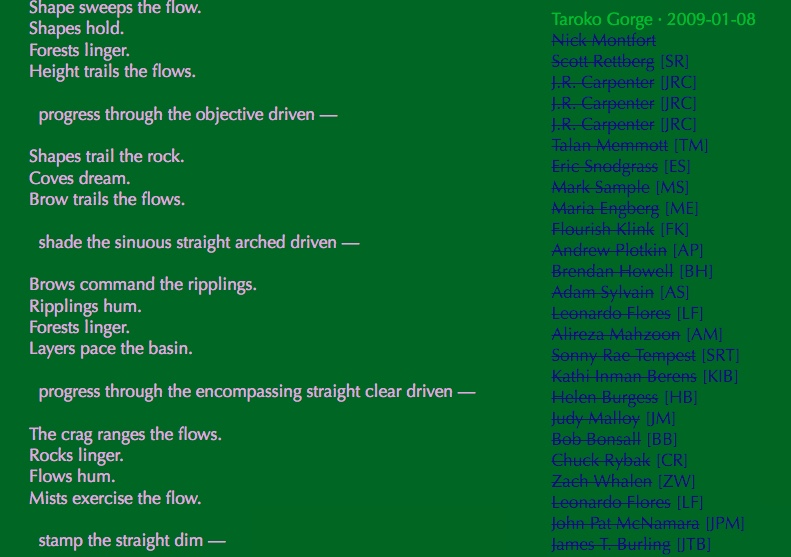

One memorable afternoon in my Digital Literature class from a couple of years ago, I introduced my students to Nick Montfort’s digital poem “Taroko Gorge.” The students watched, enchanted, as the poem’s text cascaded down the forest green page. The gentle pacing created by the gradually revealed text, together with the poem’s description of hauntingly human-like natural forces, was hypnotic. Here’s a sample of what we saw:

Shape ranges the rippling.

direct the encompassing fine cool clear —

Forests command the stones.

Ripplings hum.

Coves hold.

Stone commands the rippling.

The text continued to scroll…and scroll…and the students sensed something unusual, but couldn’t put their fingers on it. Finally, one asked if the poem has an ending at all. It does not: “Taroko Gorge” is a self-generating poem. It’s created by a single page of HTML that can run in most browsers.

This revelation—that Montfort’s text is infinite, generated by the computer from words and formulas chosen by Montfort—prompted all sorts of the questions we humanities people love. Is the poem really by Montfort? Can a computer be creative? Is the poem itself the generated words, the HTML, the interaction between the browser and the code, or the entire package? Is one instance of the generated text the same poem as another instance? Can a poem be a poem without an ending?

Rich philosophical ground aside, I want to share a particularly practical benefit of exposing students to simple computer-generated texts like “Taroko Gorge.” By clicking “File,” choosing “Save page as,” and selecting HTML (or webpage) as the format, the reader of “Taroko Gorge” can download the poem’s source code. (This should be the same in just about any browser.) Open this HTML document in any text editor, and voila: you’re looking at the poem’s guts. Here’s a taste:

function cave() {

var adjs=(‘encompassing,’+choose(texture)+’,sinuous,straight,objective,arched,cool,clear,dim,driven’).split(‘,’);

var target=1+rand_range(3);

while (adjs.length>target) {

adjs.splice(rand_range(adjs.length),1);

}

If you’re unfamiliar with code, your first thought is probably “this looks terrifying. Why would I ever show my students this?”. You may wonder how you can teach this poem when you can’t even explain how its magic is made to work. The secret? It doesn’t matter. If you bring yourself to look at the code, you’ll notice that the words meant to be inserted into the poem are fairly apparent: “sinuous, straight, objective,” etc. All that’s necessary to alter the poem is to replace these content-words with others. By doing so, you can transform the text from an ethereal nature poem to an urban wasteland, a candy kingdom, or whatever you can imagine. Yes, knowing how HTML works would allow you to understand how the poem’s syntax is generated, and even allow you to change details like font and the page’s background color. But by simply substituting some words for others, and then opening the HTML document in a browser, students can watch the new version of the poem they’ve created. On the right side of “Taroko Gorge” is a list of such remixes, which are definitely worth checking out and demonstrating in the classroom.

By showing your students that they can remix this self-generating poem, you’re not teaching them computer science. However, you are planting the seed that maybe this technology isn’t so scary after all. Maybe, just maybe, some of your students will be inspired to google HTML and learn their first few words of coding vocabulary, the better to play with the poem. This encounter with a digital text—not just looking at it, but helping create and recreate it—opens the door to a relationship with technology that is not based on fear of what seems inscrutable, but excitement at what might be possible.

Thanks to Dan Anderson at UNC-Chapel Hill for showing me and my fellow grad students “Taroko Gorge,” which inspired me to show my own students 30 minutes later.