Thinking About “Productive Failure” in Your Teaching

Pass on what you have learned. Strength, mastery, hmm… but weakness, folly, failure also. Yes: failure, most of all. The greatest teacher, failure is.

Jedi Master Yoda

In early October of 2021, I finally got around to visiting Martha’s Vineyard so I could see where the movie Jaws was filmed. I mean, to also spend some time with family and friends. But, mostly to see the locations. I have been a huge Spielberg fan since I was 10 years old, and Jaws has always held a special place in my heart. I even wrote a paper about it when I was but a wee babe in my junior year at Emerson College. You may have heard of it? Small, liberal arts school. I digress. I must have watched the film more than 50 times, and always thought I could recreate the shots, scene for scene, given the right equipment. Yet, here I was standing at the famous Jaws Bridge (yes, it’s called that), and noticing that the cloudless day was causing the water to reflect every ray of sunshine in glistening glory. The wind was strong and comforting. Both of these would have made shooting a film incredibly difficult. Nothing could have prepared me to deal with those particular variables if I had shown up that day to recreate a famous shark chomping scene. I would have failed miserably. What if, though, that was the point? What if the goal had been to realize just how ill-prepared I was to actually shoot on an island in the North Atlantic? Much has been talked about regarding active learning in the classroom. It’s grown in popularity among all branches of schooling. From K-12, to trade and vocational programs, and even has made its way to higher education. Emerson has made actively learning through co-curriculars a fundamental component of its culture. However, we need to all stand in an obvious but uncomfortable truth: all of the students are going to fail. Not only are they going to fail, but they’re going to fail over and over again across many different disciplines. Just as we all, as human beings, are prone to fail more than we will ever succeed. As Ta-Nehisi Coates is quoted in Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance by Angela Duckworth, “Failure is probably the most important factor in all of my work. Writing is failure. Over and over and over again.” What if we could take our natural inclination to fail and use it empower students and faculty alike? We can! The concept is called “Productive Failure”, and its use now is beginning to be studied more formally as an extreme form of active learning.

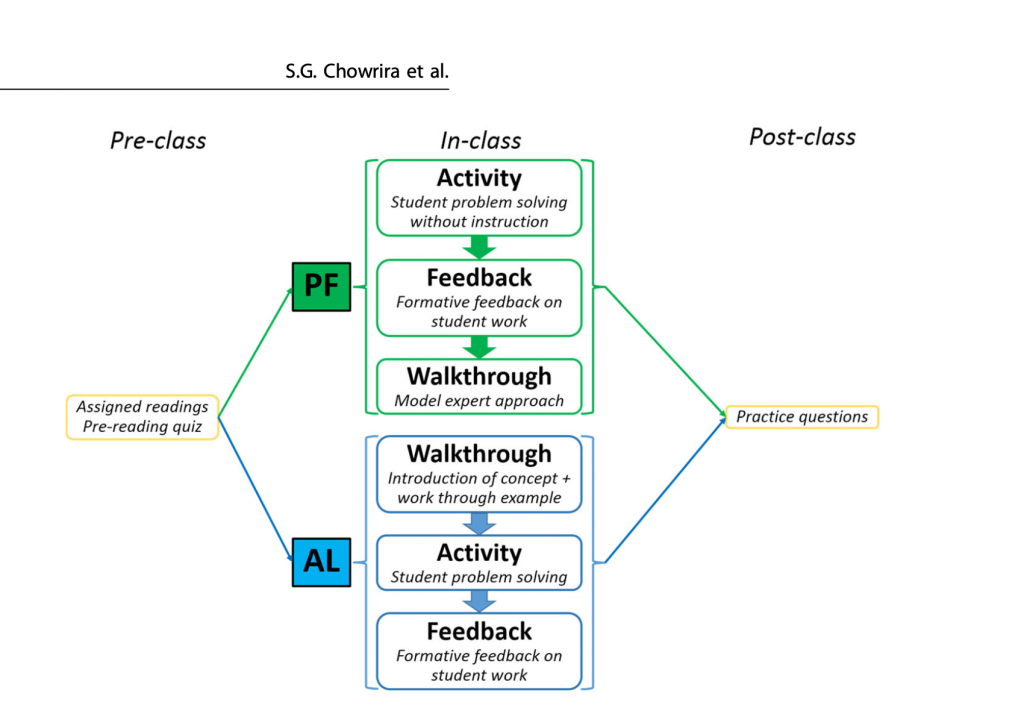

Let’s start with defining what Productive Failure (PF) is as opposed to its not-so-distant cousin, Active Learning (AL). According to an article in Nature Partner Journals: Science of Learning, “In PF, learners attempt to solve challenging problems prior to receiving explicit instruction on the target domain. While learners often fail to succeed in the task itself, it prepares them for meaningful future learning.” What does this look like?

So, what advantages does PF have over AL? From the same article, “First, PF focuses on conceptual understanding, future learning, and transferability to new topics, which are all challenging tasks for students… Second, PF seems to address other important aspects of learning at post-secondary institutions, such as fear of failing, and recovering from failure.”

Even with students engaging hands-on, demonstrating a technique or idea first before doing so still results in mistakes and failure for students. Often spectacularly. Yet, students are still grade-obsessed and afraid of failure. In the study conducted by researchers in the aforementioned article, students in a first-year class who received PF instruction as opposed to a more traditional AL instruction scored 5 points higher on average on the midterm, and then continued to show an improvement on the final exam. But, only among low-performing students. Wait, what‽ How can designing instruction where the goal is to make students fail possibly help low-performing students? This is where I get to get on my soapbox and make the connection between PF and fostering a “growth mindset” versus a “fixed mindset” in students.

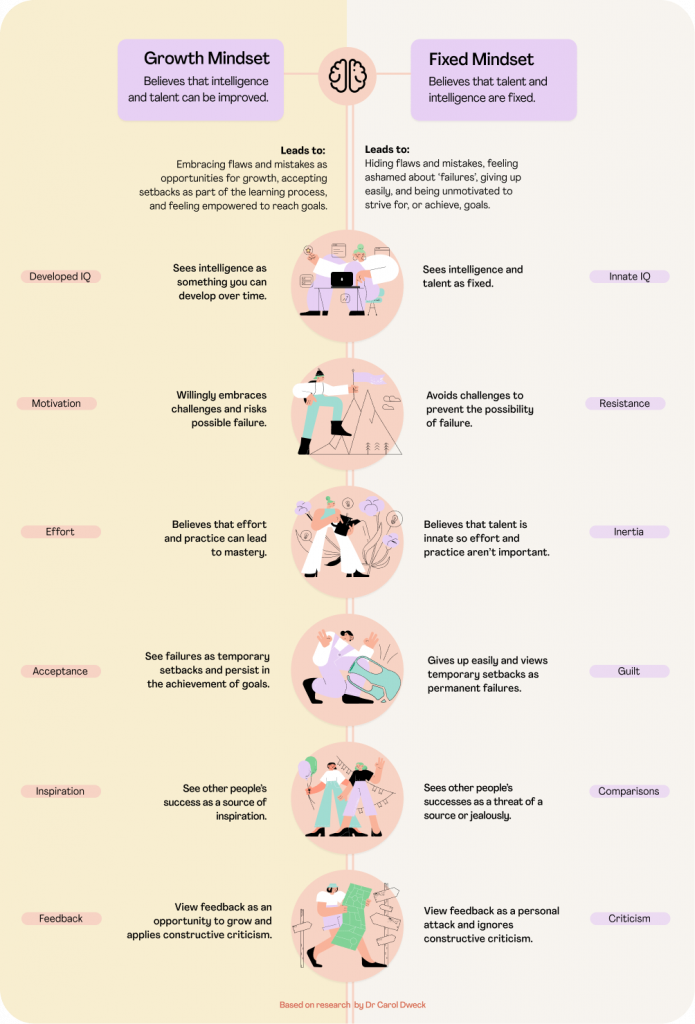

So much has been written about growth versus fixed mindset in education, trying to point to any one book, article, or journal is like trying to find the best grape on a vineyard. Though, it was Carol Dweck who was the original vine, and her work has been massively influential in not just higher education, but just about everything!

As you can see from the above chart, a growth mindset is clearly more helpful for not only learning and adapting, but also for handling setbacks. With pushes towards more equitable teaching in classrooms, PF also has the side-effect of helping to get all of the students on the same page, regardless of backgrounds before college. The shared knowledge that the goal is to fail, with full permission to experiment, question, and synthesize with what they already have, students with anxiety, disadvantaged backgrounds, and even cultural inhibitions will be approaching topics the same as their more privileged peers. However, there is an obvious caveat. In his book How Humans Learn, Joshua Eyler writes:

We cannot give students a task that lies so far outside their cognitive experience that they have no entry point for tackling it. Instead, we are interested in those moments of failure that are actually conducive to further learning. In order for this to happen, the challenge we give students must be accessible to them either through prior knowledge or scaffolded coaching, and it must also be generative in building new networks that serve to enhance students’ conceptual understanding.

Of course that makes sense. But, where is that line? This is where you as a subject-matter expert (as we say in Instructional Design lingo) come in. Is it a chapter from one of Foucault’s many books? Or is it a video of a monologue from a stage production? Or perhaps it’s to watch Jaws a hundred times so that some poor film enthusiast could recreate it in their head easily? The next part is where the “art” of teaching comes in. What are some of the common mistakes you’ve made, or seen your peers make in your field? What are things that can really make a film shoot go belly up? Spielberg would say it was a mechanical shark that never did seem to work, forcing him to partner and collaborate with his composer to see if there was a way to make the music stand in for the puppet. We know how that turned out. Setting your students up to make these kinds of mistakes within a safe context is something that is hard to fully plan out, as individual class compositions could make prior knowledge of the subject very variable. The chances of you having to adapt on the fly and adjust is a given, but also gives you immense flexibility in the kinds of discussions and exercises you can provide your students.

Want to talk more about leveraging the power of failure in the classroom? Feel free to contact ITG!