Why – and how – to teach students to reflect

Written by Liz Chase and Natalie Hebshie

Your students see that they’ve been assigned a “reflection” as part of your class. This usually prompts a range of reactions from my students: “Oh good, this will be easy.” “Ugh, I already did the assignment, why do I have to think about it more?” “I already over-analyze everything, just tell me my grade.” Reflections can also become one more thing for us to grade. At their best, though, they’re an equity-centered means of breaking down the power dynamics of grading by turning feedback into a conversation between student and instructor.

Many Emerson classes already make use of reflection assignments. Here, we’re going to outline additional ways to enhance the transparency of these assignments and make them meaningful to students. If we don’t ask students to “think seriously about their experiences,” reflecting on how those experiences alter and shape their understanding of themselves and their work, our teaching may inadvertently “reinforce stereotypes and incorrect suppositions” (2).

In a 2018 article in the Journal of Instructional Pedagogies, Mark Young writes: “hands-on experiential learning activities are congruent with today’s students’ mental aptitudes and skills, [however,] converting these experiences into deep learning through deliberate reflection and abstract conceptualization is not” (2). On the flip side, recent pedagogical research tells us that engaging students in self-reflection enhances their intrinsic motivation to learn and their ability to connect that learning to their personal goals (8). The benefits are numerous, and thankfully, incorporating self-reflection practices does not have to be a labor-intensive part of your assessment tool-kit. The options outlined below range from the least to most time intensive; all can be used separately or as part of an integrated effort to encourage deep learning and critical self-assessment.

Idea #1 – The (Five) Minute Paper – Simplest

Many faculty already use minute papers or clearest and muddiest point exercises as quick, informal checks of students’ understanding. The same minute (or more realistically, five-minute) paper can easily be adapted to provide a low-impact, immediate format for feedback.

Suggestions:

-

- Select a learning outcome from your course; i.e., in a course on “Memory and Violence in Modern Ireland,” a central outcome is that students can: “Explain the ethical and moral issues that memory and commemoration raise in the wake of violence.”

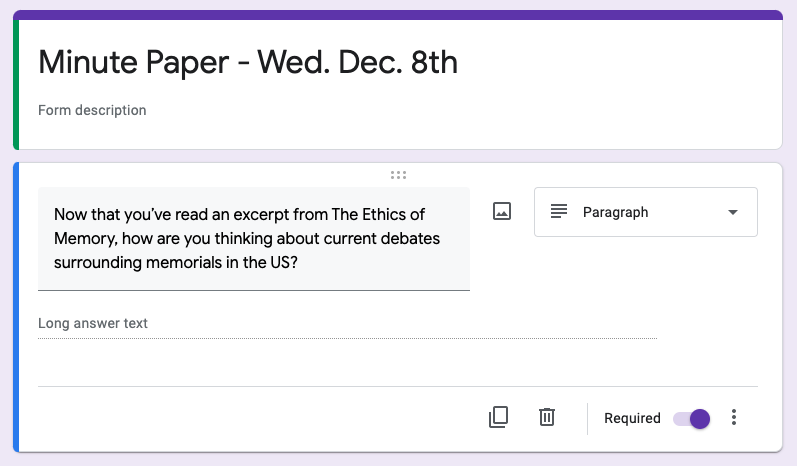

- Define a specific question linked to that outcome, with a manageable scope; i.e., “Now that you’ve read an excerpt from The Ethics of Memory, how are you thinking about current debates surrounding memorials in the US?”

- Ask students to spend five minutes in-or-outside of class writing their response.

- Keep responses anonymous and ungraded; the goal here is to build students’ capacity for critical self-reflection and awareness, and gain insights into areas where they may be struggling. Doing so anonymously and without a formal grade attached helps them practice skills used in the additional exercises described below.

- In a subsequent class session, share the main threads from student responses and discuss how they relate to the course outcomes and your goals.

How the (Five) Minute Paper Looks Digitally

There isn’t a way to have an assignment in Canvas be completely anonymous. If you’d like to collect your Minute Papers digitally and have them be anonymous, there are a few tools available to you with your Emerson account:

Google Forms

Google Forms are a good option for collecting anonymous submissions. Your form will consist of one paragraph-style question. If you’re going to be collecting minute papers on a regular basis, we recommend using a consistent naming convention so that you can tell your forms apart.

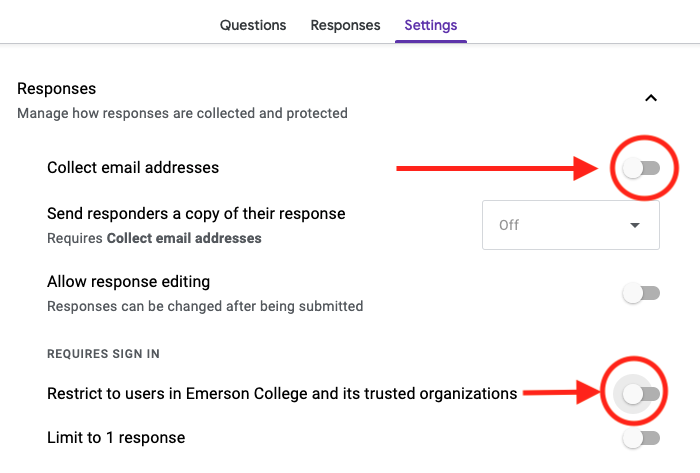

To make sure that Google does not collect identifying information, check that the “Collect email address option” and “Requires Sign In” is disabled in the form’s Settings.

When you’re ready to share your form with students, click the Send button and then the Link icon to access the form’s shareable link. Once you have your link, you can post it to your Canvas course via the Announcements tool.

Qualtrics

Qualtrics is a more advanced survey tool available to Emerson users via qualtrics.emerson.edu. For this particular activity however, the general idea is the same as Google Forms; the advantage of Qualtrics is that it offers sophisticated data analysis tools for those interested. If you’d like to explore Qualtrics as an alternative to Google Forms, contact Liz Chase.

Idea #2 – Assignment Cover Letter – a little more time intensive

The assignment “cover letter” requires slightly more time; its primary benefit is that it opens a conversation between students and faculty and encourages students to see the grading process as a step in their learning process. Here, students are asked to reflect on their work and the process they engaged in; the assignment cover letter also allows you to see how they are approaching their work and whether that approach embodies the outcomes and perspectives you set for your course.

Format:

When students submit a project, paper, draft, etc., they also submit a brief 1-2 paragraph “cover letter.”

Sample questions:

In your cover letter, please address the following:

-

- Describe how you approached this assignment. What steps did you take? What questions did you have?

- What aspects of your work are you pleased with?

- What are 1-2 aspects of your work that you found challenging and would like me to provide constructive feedback on?

Suggestions:

-

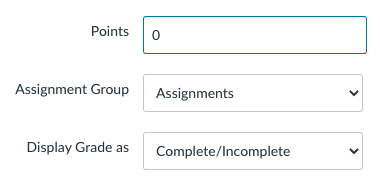

- If the cover letter is assigned points, grade it as completed/not completed; this keeps the emphasis on the conversation itself and encourages students to be open and honest, taking risks in learning to describe their process, strengths, and weaknesses.

- Note if/when you agree with the student’s self-assessment of their strengths in your feedback.

- Highlight places where you’ve provided the feedback students requested.

- Choose 1-2 additional aspects of the work to respond to in order to keep feedback manageable.

How the Assignment Cover Letter Looks in Canvas

You can either create an assignment just for the cover letter, or have students attach it to their main submission. Creating a separate assignment allows you to give it a separate grading scheme. For example, in your assignment details, you can select Complete/Incomplete for the Display Grade As setting. Then, set your Points to 0 (or a small number of points).

This allows you to easily track that the student submitted their cover letter while keeping the grading low stakes. It also allows you to view both submissions in two separate windows side by side.

If you prefer to keep everything together, you would simply ask your students to include the cover letter as part of their assignment submission. It’s important that they submit their cover letter and their paper/project together as one submission since Canvas does not have a way of collecting multiple components as part of one assignment. (The most recent submission simply overwrites older submissions.) If you’re using a rubric to grade your assignment, you can include the cover letter as one of the criteria so that it’s incorporated into the grade for the assignment.

Idea #3 – Self-Assessment Rubric

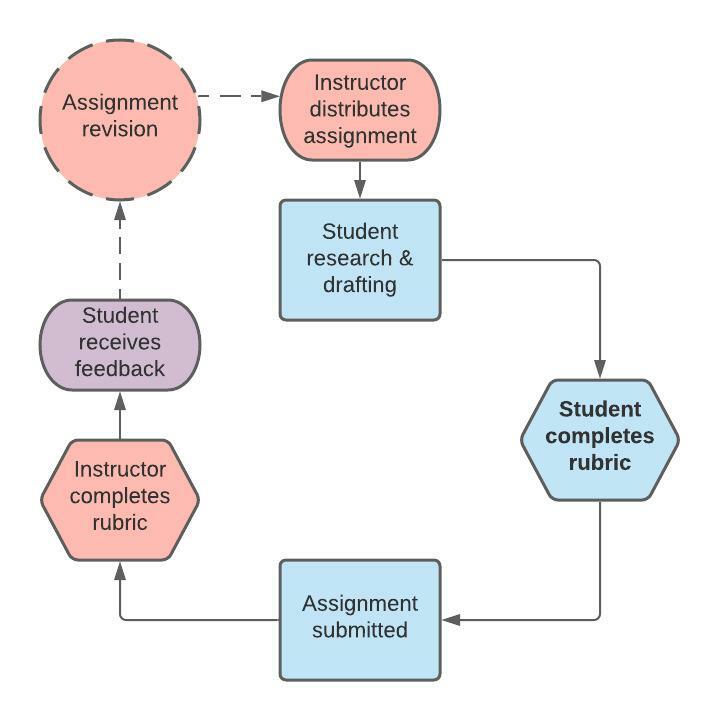

The self-assessment rubric is the most time-intensive, and has the advantage of being the most focused on encouraging students to approach evaluation as a conversation between student and instructor. In this practice, when you distribute an assignment, students receive the rubric or evaluative measure (assessment form, grading schema, etc.) that will be used to grade their work. The rubric and assignment are both discussed in class for clarification. Then, when students submit their work, they are asked to evaluate and grade their own work. Additionally, they are asked to write a brief justification for that grade. Adding this step to the normal process of receiving an assignment, completing work, and submitting it for grading asks students to pause and reflect: they are encouraged to develop their skills of critical self-assessment.

The assignment is then submitted to the instructor, who also completes the rubric and articulates for the student where their evaluation differs from the student’s self-evaluation and why. Some instructors might choose to meet with students to discuss the evaluations, or encourage students to revise and resubmit their work based on the feedback provided. The value in this process is that it not only encourages students to develop the capacity to self-assess, but also mirrors the back-and-forth of critique and response they’ll need to navigate in their professions. Last but not least, it enables instructors to see how students are interpreting the assignment and make adjustments as needed.

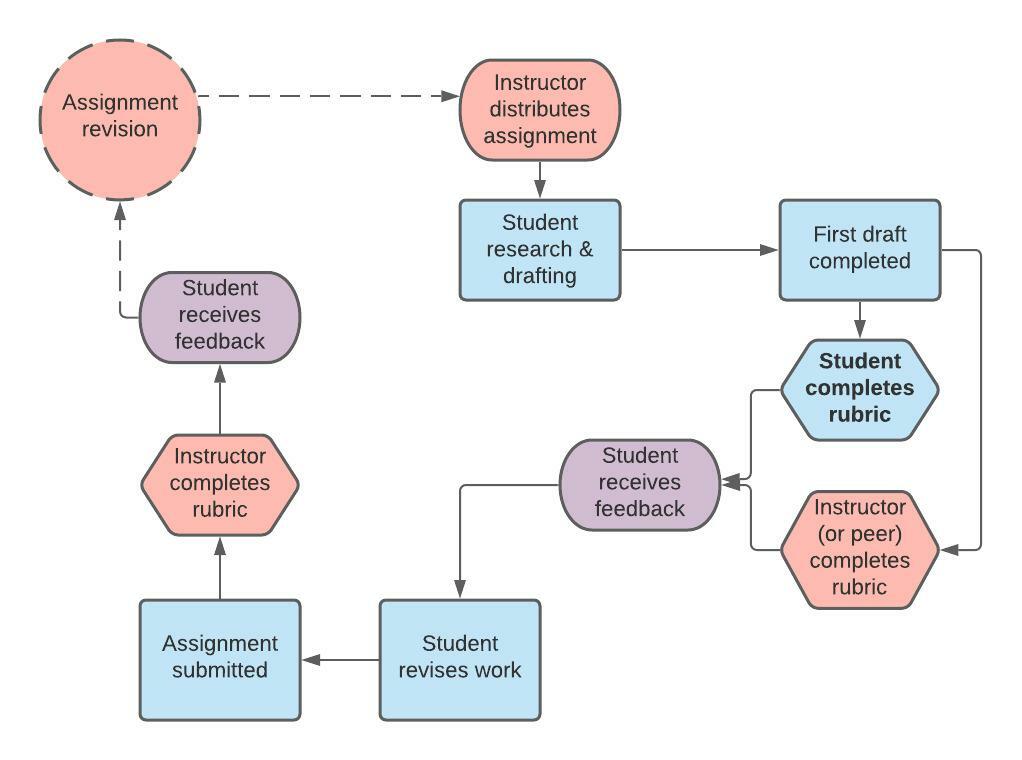

This process could also look like this: students can complete the rubric at the draft stage, get additional feedback from peers or the instructor, and use that constructive criticism to improve their work (perhaps with the cover letter attached detailing how they revised and reassessed their work).

How Self-Assessment Looks in Canvas

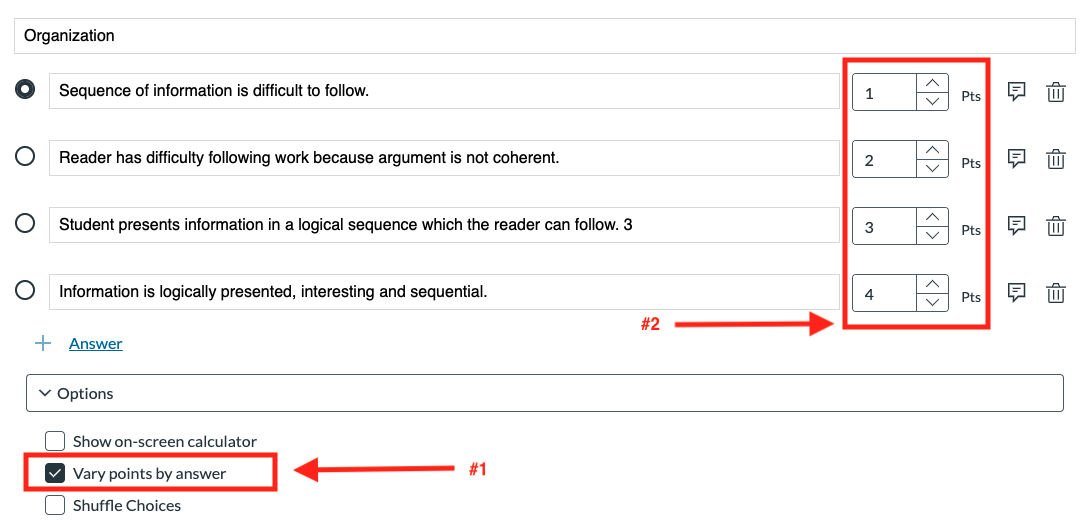

Unfortunately the Canvas Rubrics tool doesn’t have an option for self-assessment that students can fill out. However, one work-around is to use Canvas’s New Quizzes feature to create a form for students to complete. When creating the quiz, you’ll want to do the following:

- Check “Do not count this assignment towards the final grade.” This will allow some breathing room for some back-and-forth between you and your students as you discuss their grades with them.

- Choose “Multiple Choice” style questions. Then, add your criteria as the possible “answers.”

- Check off the “Vary points by answer” box at the bottom of each question. This will allow you to give each criteria a numerical value. Here is an example of what that might look like:

If you’d like Canvas to tally the score for you, you can stick to multiple choice questions with numerical values for each criteria. However, you could include an open-ended essay-style question for students to share the grade they think they should receive and any additional information that you should be aware of.

Conclusion

If you’re interested in discussing how reflection might fit into your course goals and objectives, feel free to schedule a consultation with Liz Chase, Senior Associate Director, Office of Academic Assessment, liz_chase@emerson.edu. These practices hold a lot of potential to address some of the questions about grading and equity raised by students and faculty during the Fall 2021 Teach-In on Race!

For help implementing any of the above ideas into your Emerson Canvas course, reach out to ITG: itg@emerson.edu or 617-824-8090.

References

Young, Mark. “Reflection fosters deep learning: The ‘reflection page & relevant to you’ intervention.” Journal of Instructional Pedagogies, vol. 20, May 2018, 1-20. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1178730.pdf